TAKING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING ONLINE: STUDENT PERCEPTIONS

University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

*Address all correspondence to: Patricia Danyluk, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, E-mail: patricia.danyluk@ucalgary.ca

This article examines the impact of an online field experience course designed for Bachelor of Education students during the COVID-19 crisis. When Alberta schools closed two days before preservice teachers' practicum was to begin, all 435 in-school placements had to be canceled. To ensure students were able to progress in their program without disruption, the authors designed a unique online course to replace the traditional in-school practicum. This mixed-methods research study explores the key findings of an online survey of preservice teachers who made the shift to an online environment. The data included examination of course documents and discussions with instructors during weekly community of practice meetings. Through the innovation of the newly created online practicum course, preservice teachers developed an enhanced appreciation for online learning. However, in the absence of kindergarten to grade 12 students, the online practicum was unable to provide some of the more practical aspects of an in-school practicum. The authors have begun to explore a gap in preservice teacher education, which they have coined digital instructional literacy.

KEY WORDS: online learning, practicum, pandemic, pandemic practicum

1. CONTEXT

In March 2020, universities and schools across Canada were directed to change from face-to-face (F2F) learning to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Doreleyers & Knighton, 2020). The period that followed this announcement has been described as “chaos, panic, worry, apprehension and insecurity” as educators, largely untrained in digital pedagogies, moved their courses online and adjusted to new technologies (Kidd & Murray, 2020, p. 547).

While the majority of post-secondary courses were able to shift somewhat easily to online delivery, providing an alternative to the in-person teaching practicum was more problematic (Van Nuland et al., 2020). In the province of Alberta, Canada, schools were directed to close by public health officials on Friday, March 13, 2020, just two days before the first-year preservice teacher participants were to begin their second practicum in schools. As partner teachers and principals were faced with the challenge of managing digital instruction for thousands of young children and youth, the practicums of preservice teachers were relegated to a secondary concern for schools.

School boards in Alberta were not yet offering online teaching for kindergarten to grade 12 (K–12) students; therefore, they were both unable to provide and unwilling to support placement opportunities for our preservice students in online environments. The consequence of not providing an alternative to the in-school placement would be that all 435 of the students in the Alberta schools would need to delay their program, and this delay would have financial repercussions for cash-strapped students by extending the time before they could complete their degree and move into the workplace. Postponing or canceling the practicum would impact the degree progression of the 435 Bachelor of Education students in the program; therefore, the decision was made to move this fully experiential course into an online learning environment. We, the article authors, had 36 hours to develop a solution for presentation to senior administration with the intention of launching it the following week.

2. COURSE DESIGN

Over 36 hours, the authors worked together to create the new course with the intention of retaining the experiential nature of an in-class practicum. After gaining approval from the faculty senior administration, the course was launched on March 23, 2020, and was thereafter informally referred to as the pandemic practicum (Burns et al., 2020). The focus of the newly designed course was to address concerns faced by preservice teachers in their F2F practicums in an online environment. The course objectives focused on areas that preservice teachers often struggled with in F2F classroom settings, namely, designing for differentiation and incorporating Indigenous perspectives. These two objectives are key competencies in the Alberta Teaching Quality Standard (TQS) (Alberta Education, 2018)—a mandated document that guides teacher professional practice and provides a framework for the preparation, professional growth, supervision, and evaluation of all teachers. The TQS lists six competencies for Alberta teachers: fostering effective relationships; engaging in career-long learning; demonstrating a professional body of knowledge; establishing inclusive learning environments; applying foundational knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples; and adhering to legal frameworks and policies (Alberta Education, 2018).

In this teacher education program, preservice teachers complete four mandatory practicums prior to graduation. The practicum courses are designed to gradually increase the amount of time and responsibility that preservice teachers assume as they develop their teaching identity and practices. In their first practicum, preservice teachers spend two weeks observing the work of teachers and students in K–12 settings to understand current trends in education and the realities of the classroom. By their final practicum, they assume up to 100% of instruction as well as the other duties of a teacher.

The original course design of the second practicum was intended to be an introduction to lesson planning and teaching in K–12 school settings. In this four-week practicum, responsibility for lesson planning and teaching increased gradually, and by the conclusion preservice teachers were teaching up to 30% of the day. The newly designed course or pandemic practicum sought to replicate teaching experiences by providing preservice teachers with opportunities to create online lessons and teach to their peers as well as to the whole class.

During each week of the pandemic practicum, preservice teachers participated in at least one synchronous session. Each week, preservice teachers completed reflective assignments based on course activities and engaged in discussion posts based on course readings. In the first week of the course, preservice teachers focused on personal wellness as they examined well-being and the teaching profession. In incorporating the topic of personal wellness, the authors sought to acknowledge the stress of living in a pandemic and provide opportunities to discuss self-care. In the following week, preservice teachers designed and delivered an online lesson in small groups. Following feedback from instructors and peers, preservice teachers completed a reflective assignment that required them to consider how their lesson could be improved. The third week of the course focused on creating a positive classroom environment and exploring resources for incorporating Indigenous perspectives into their lesson design. Knowing that preservice teachers would complete a course on Indigenous education in the final year of the program, it was important not to overlap with that course but instead enhance it by providing more time to explore and share resources. In the final week of the course, preservice teachers designed and delivered a lesson to the whole class that addressed issues of diversity and inclusion.

Twenty-two field-experienced instructors—largely contract faculty instructors who were retired teachers and principals—had been hired to observe the 435 preservice teachers teaching in classrooms prior to the closure of schools. While there was a variety of experience with online teaching in the group, there were several instructors who had never taught in an online environment. To ensure the quality of the delivery of the course, the authors created a community of practice, whereby instructors would share resources and ideas each week. Wenger et al. (2002) described communities of practice as “groups of people who share concerns, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 4). Prior to the course launch, the authors met with the course instructors to outline the newly designed course. In each of the following weeks, the authors led a series of community of practice meetings during which course content and delivery were discussed and resources were shared. On two occasions, guest speakers were invited to provide tutorials on technological features available to instructors during synchronous sessions.

Recognizing this as a unique opportunity to better understand student learning, the three authors launched a scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) research study during the final week of the course. By drawing on student surveys, course outlines, and design discussions, the authors examined preservice teacher perceptions of the transition to the online learning environment as well as the impact on learning.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

When COVID-19 led to the closure of post-secondary institutions across Canada, it had a tremendous impact on students as courses were moved online or canceled altogether (Doreleyers & Knighton, 2020). Examining the impacts on post-secondary students in Canada, Wall (2020) found that almost 60% of preservice teachers expecting to graduate experienced the cancellation of their practicum. At the same time, over 30% of education students at other stages in their preservice program experienced the cancellation of their practicum. The shift to online learning posed challenges for many post-secondary students, who reported that they learn better in F2F courses, and others, who lacked appropriate tools and or did not have a suitable home environment for online learning. For many of these students, the stress of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic was compounded by the stress of adjusting to online learning (Doreleyers & Knighton, 2020). This finding is consistent with the results obtained in Xu & Jaggars (2014), which indicated that online courses are more likely to result in student disengagement and eventual failure.

Students in post-secondary professional programs are reluctant to engage in online learning since they fear it will diminish the quality of their degree (Compton et al., 2010). Those who continued with online learning during the pandemic had concerns regarding their grades, their ability to complete their credential, and the value of their credential (Doreleyers & Knighton, 2020). Kidd and Murray (2020) described the closure of schools and the halt of traditional practicum experiences, as creating a “curriculum” and “pedagogical vacuum” for student learning (p. 547). Issues such as student well-being, the impact of missing the practicum, concerns about the quality of online instruction, and meeting licensing requirements (Kidd & Murray, 2020) were brought to the forefront.

Preservice teachers look forward to engaging with students and teaching in the classroom (Van Nuland et al., 2020). In fact, for most preservice teachers, the practicum is viewed as the most valuable component of their teacher education programs (White & Forgasz, 2016; Ralph et al., 2009; Schulz, 2005). Extended time in practicum working alongside experienced teachers is directly connected to better prepared teachers (Darling-Hammond, 2014). The practicum provides preservice teachers with the opportunity to address spontaneous problems, make decisions, manage the classroom, and develop a professional vision (Smith & Lev-Ari, 2005). These aspects of teacher education are not easily duplicated in an online environment.

Kennedy and Archambault (2011) reported that 1.3% of teacher education programs in the United States offered virtual field experiences to preservice teachers pairing them with online students. Preservice teachers engaged in virtual field experiences reported increased confidence in online instruction and the ability to differentiate to meet student needs. A consistent concern among preservice teachers was the absence of a sense of community in their online practicum (Wilkens et al., 2015). This sense of community within an online practicum is crucial to students' perceptions of success within the course (Jackson & Jones, 2019).

Preservice teachers typically resist online learning since they view it as providing limited interaction with their instructor as well as reduced feedback from their instructor (Compton et al., 2010). Although it is assumed that as digital natives preservice teachers have the skills, motivation, and competencies to effectively use educational technology in an online environment, this is not always the case (Prensky, 2001). While preservice teachers may have grown up using computers, they do not necessarily understand how to use technology as an effective instructional tool (Burns et al., 2020). Adding to the complexity, undergraduate students are often confused about their roles in online learning (Armstrong & Mulvihill, 2007) and require clear direction from their instructors on how to interact with the course material. Furthermore, students in rural and remote parts of the province often experience slow Internet service and their service is more likely to be disconnected due to limited access to broadband Internet service (Van Nuland et al., 2020). Setting students up for success in online learning necessitates additional work for faculty teaching online.

In an examination of higher education's response to the pandemic in Canada, Metcalfe (2020) reported that during the shift to online learning, faculty workloads increased by at least 50%. At the same time, faculty experienced new concerns related to working from home, including shared work spaces, caregiving duties, and locating the hardware required to teach from home (Metcalfe, 2020). Since academics are experts in their chosen field and not necessarily equipped with the technological and pedagogical skills to teach online (Van Nuland et al., 2020), many post-secondary educators found themselves learning new technological tools. Faculty are often reluctant to teach online since they perceive developing an online course as more time intensive than developing a F2F course and are reluctant to volunteer for the additional work (Chiasson et al., 2015). Faculty with little experience teaching online possess a limited repertoire of strategies for online learning, often consisting of lecture, case studies, and research (Fish & Gill, 2009). With more experience teaching online, that repertoire expands to include group discussions and group work (Fish & Gill, 2009).

In designing the course, the authors created assignments that required preservice teachers to design lesson plans, deliver lessons in small groups as well as to the whole class, reflect upon their design and delivery, and engage in online discussion posts. Garrison et al. (1999) pointed out that among the many advantages of written communication in online courses it permits time for reflection and critical thinking (Garrison et al., 1999). In their examination of online teaching practicum, Jones and Ryan (2014) found that the type of online discussion posts students engaged in impacted their learning. Structured discussions such as threaded discussion posts were more likely to result in reflective practice than blogs. The questioning, reasoning, deliberating, and challenging communications that occur in online discussions lead to high-order thinking (Garrison et al., 1999).

4. METHODOLOGY

This study draws upon a scholarship of teaching and learning framework since the purpose was to determine how preservice teachers in the pandemic practicum perceived the course, whether or not their perceptions shifted during the course, and finally, if they shifted, how? The SoTL involved inquiry into student learning used to inform practice (Hutchings & Shulman, 1999) and a “systematic reflection and study of teaching and learning made public” (McKinney & Jarvis, 2009, p. 1). The SoTL acted as a bridge between research and teaching by engaging in research about teaching (Hutchings et al., 2013). Engaging in SoTL research has been directly linked to enhanced student learning—meaning that students are the beneficiaries of a scholarly approach to teaching (Trigwell, 2013). Felton (2013) identified the common principles of good SoTL as extending beyond inquiry into student learning and including being grounded in context, methodologically sound, conducted in partnership with students and appropriately public. Through the SoTL lens, the authors sought to develop deeper understanding of preservice teacher learning in this course and to use this information to reflect upon the results and adapt the design of the practicum courses that followed.

This study utilized a mixed-methods methodology in the form of a survey with both qualitative and quantitative questions, document study, and discussions with instructors (Cresswell, 2015). This article focuses on the analysis of the survey data. After institutional ethics were received, data were gathered through an online survey using the Qualtrics survey software; document analysis of the two course outlines, including the previous year's outline for the course and the newly designed pandemic practicum outline; and reflection on discussions during our community of practice meetings. Using Qualtrics for the survey ensured that all responses were anonymous and could not be linked to a specific participant. In order to lessen any power dynamics, the invitation to participate in the survey was sent out by the field experience office. The survey focused on the following research questions:

- Did preservice teacher perceptions of online teaching and learning change through participation in the online practicum course?

- What did preservice teachers perceive as their greatest learning during this online course?

- How can the preservice teacher perceptions of their learning experience inform future field experience course planning?

5. FINDINGS

In total, 228 students completed the online survey for a 52% response rate. The more significant finding was that although initially disappointed with the shift from the in-school practicum to an online practicum, the majority of students reported a positive shift in their perceptions of online learning. Further analysis of the data pointed to five themes: shifts in perceptions of online learning, need for preparation for future teaching, areas where the most significant learning occurred, skills developed, and suggestions for how to improve the course.

5.1 Shifts in Perceptions of Online Learning

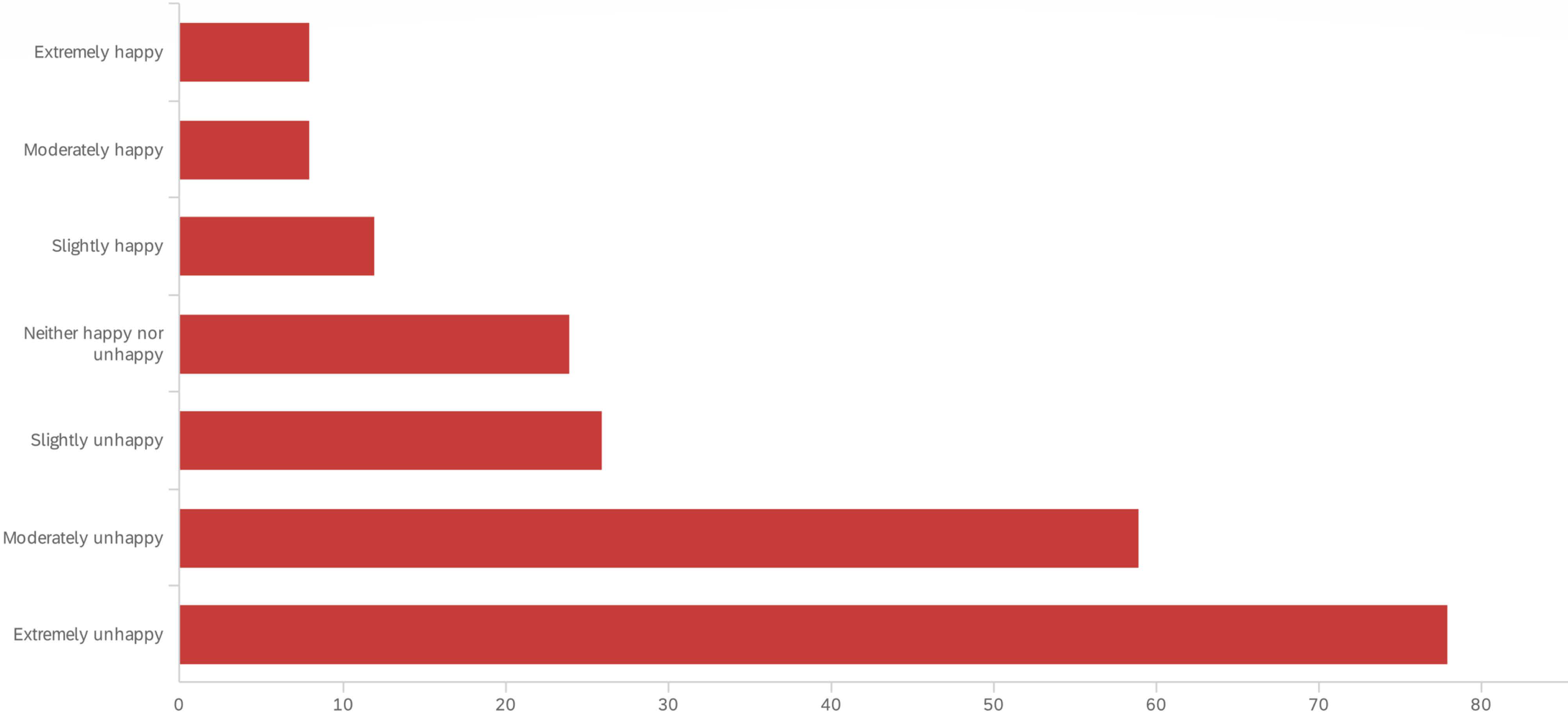

Preservice teachers in the course were deeply disappointed when they learned that their in-classroom practicum was being replaced by an online course, which became known as the pandemic practicum (Burns et al., 2020), with 38% indicating they were extremely unhappy. Responses to this question were significant since they provided a context for all other responses in the survey (Figure 1). The fact that participants were disappointed in the cancellation of their in-school practicum was not surprising. The bigger question was: could this disappointment be minimized through a well-designed course that provided opportunities to teach online?

FIG. 1: Initial reactions to the shift to an online practicum

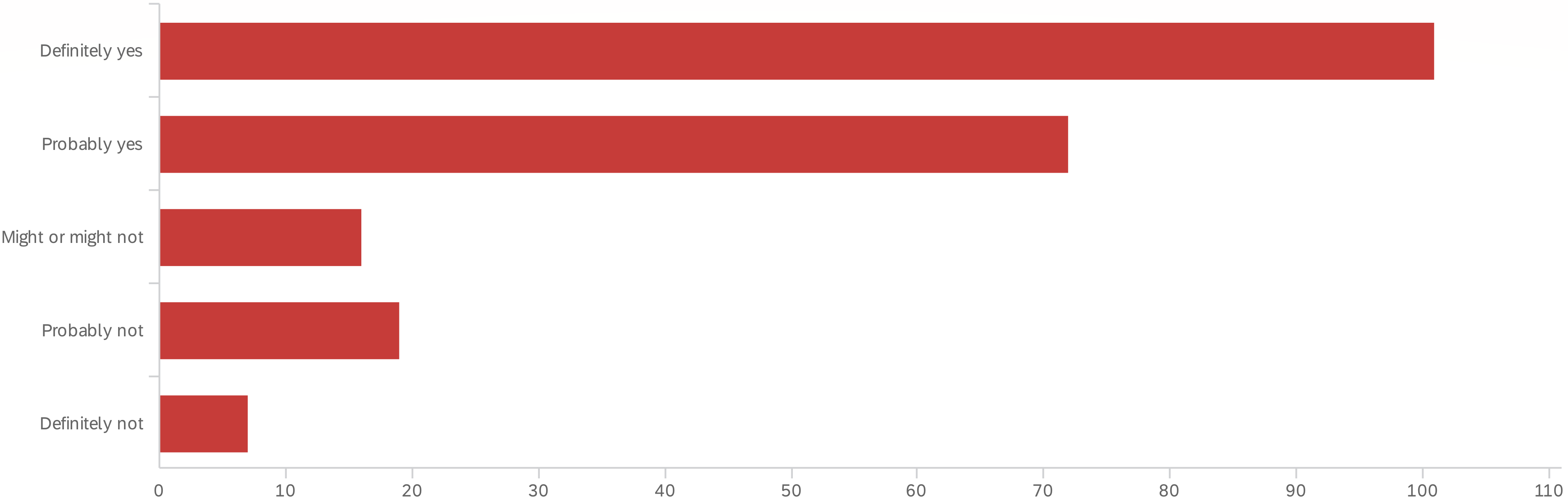

At the conclusion of the pandemic practicum, 44% of respondents indicated that the course had definitely shifted their perspectives of online learning (Figure 2), while another 31% indicated it had probably shifted their perspectives of online learning. In response to the question, did your perception of online learning change during this course, the comments indicated that the shift in perspectives was largely positive, with 100 respondents indicating the course had shifted their perspective of online learning and another 70 respondents indicating the course had probably shifted their perspectives of online learning. The following quotations from participants are representative of the largely positive responses to the question: “my perception about the effectiveness of online learning improved greatly. The course went smoothly, and I still felt as though I was able to get to know my instructor and cohort.” Still another preservice teacher commented, “It made me realize students can still engage, participate and learn a lot through online learning. As teachers, it was a valuable experience to have and to gain/learn from as well because it tests our adaptability.”

FIG. 2: Shift in perceptions of online learning

5.2 Did Your Perception of Online Learning Change during This Course?

Several participants indicated that they were surprised by how interactive an online course could be. One respondent described the interactive nature of the learning as follows:

My perception of online learning prior to this course was of students working through online modules individually before working through multiple choice online quizzes as this was my experience with an online course in high school. Now however, I have seen just how engaging online learning can be. There was a high level of teacher-student contact and high amounts of diversity regarding lessons and activities.

Another participant explained that through the course he/she became aware of the diversity of teaching strategies available in the online environment: “I originally expected it to be completely lecture based and revolve around a summary of the work done this year and how it culminates into preparation for real-world application, but was instead more free flowing and open-ended in how we used the experience.”

5.3 Preparation for Future Teaching

At the time of the survey (April, 2020), it was unclear how long the pandemic would last or how long online teaching would continue. Respondents were asked to consider whether this course prepared them for the future of learning. Depending on how they interpreted the question, the future might include online learning or it might involve a complete return to the classroom. Responses to this question were largely positive with the majority of participants indicating the course prepared them for the future of teaching. The majority of the respondents reported that they found value in the opportunity to practice teach in front of peers, indicating:

Yes. The opportunity to practice teaching in front of informed colleagues and receive their feedback—as well as the opportunity to observe, critique and most of all help and encourage one another as colleague student-teachers, was highly valuable, and might not have been as readily achieved (as a collaborative cohort) using the original field course structure.

For students who envisioned the future of teaching having some element of online practice, the course was valuable, with one student commenting, “I believe it prepared us for a different type of teaching, but not necessarily for traditional classroom teaching.” Other responses pointed to the value of the course, while at the same time expressing a sense of loss over not being able to be in the classroom. One student indicated the course prepared him/her “for sure for online teaching, but not for other aspects like building rapport with people,” while another shared, “Somewhat. Very helpful if I ever have to teach online. I'm sad to miss out on classroom experience.”

As with other questions, there was a strong sense of disappointment, with 10% of the respondents expressing frustration and anger at having to complete the pandemic practicum, pointing to the inadequacy of the course to prepare them for practical aspects of teaching. One preservice teacher commented, “I was disappointed not to be able to learn from my partner teacher and observe him in the classroom” and another stated, “Nothing can take the place of being in an actual classroom and teaching real students.”

5.4 Areas Where Learning Occurred

Overall, participants indicated that the most impactful learning that occurred through the course was learning how to teach online. As one student commented, “If I were required to teach anything online at all, then I now know how I could go about doing so.” Another preservice teacher described becoming more open to different ways of learning stating, “it prepared me in a way that it made me change my attitude towards certain situations and gave me an opportunity to experience and prepare for an online learning situation.” In their survey responses, preservice teachers expressed a growing understanding of the labor-intensive work involved in teaching online, with several commenting that teaching online was “much harder than it seemed” and another sharing “I did not realize what a difficult process it was to switch dramatically to an online platform.” Coupled with the behind the scenes work required to plan a good online lesson, preservice teachers expressed disappointment when their Internet connection was disrupted during their lesson delivery. Although they were often able to work around technological glitches, it was frustrating for those who had worked hard to prepare a seamless lesson, only to see it disrupted by issues outside of their control.

Several respondents commented on the value of practicing an online lesson in front of peers and receiving feedback on how to improve the lesson. One student shared “the advice of peers is critical to ensure you cover areas you may not have considered” while another indicated “It was valuable to have to teach online and to get feedback from my peers.” Preservice teachers described appreciating the way in which the course emphasized lesson and unit planning and the role that observing their peers played in their learning. One respondent described it in this way:

The opportunity to observe, provide an online lesson as well as watching my cohort was a major part of the learning experience. Recording lessons on Zoom is a very good way to practice timing, pacing, delivery, and observation of emerging teacher presence.

As with the other questions, there was a contingent of responses that indicated anger with having to complete the course online, with one student expressing frustration in this way: “I do not feel that doing Field II online is an appropriate or equivalent experience to being placed in a classroom with students.” Much of the disappointment experienced by preservice teachers was centered around not being able to learn practical aspects of teaching, which could not be duplicated in the online environment. As one student commented:

I feel it didn't come close to the experiences and feedback that we would have been able to receive if we were in our placement schools. We didn't have the hands-on learning with students and the different demands and accommodations we would have examined.

Another student stated, “I feel I need the hands-on experience of classroom teaching.” Preservice teachers pointed out that as a result of the lack of hands-on experience they recommended the next practicum be designed with a more gradual immersion into teaching responsibilities:

I do not feel more prepared for teaching. I did grab a stronger aspect on lesson planning and what day-to-day teaching will look like. However, as for my skills as a teacher inside the classroom, I feel less prepared to teach in the future. But I would be fine if maybe there was more leniency on our teaching in our field 3 experience! Maybe a week where lesson planning and discussion can take place and transition slowly.

A surprising finding from the survey data was the way in which the course resulted in unexpected learning about the teaching profession including the importance of flexibility and being able to adapt to circumstances, as one preservice teacher stated,

While I don't think there is any true replacement to hands-on in-classroom teaching experience, this course was an exercise in flexibility and my ability to adapt and face adversity in a positive way. I know that my future career will have many ups and downs and that things won't always go the way I hope they will. I hope that this experience will help remind me that I am capable of teaching even when circumstances aren't ideal.

Similarly, another respondent commented, “I was reminded that some of the most important aspects of being a teacher include being flexible, open minded, having a positive attitude and creating a community.” The course also led to realizations about the nature of change and the importance of collaboration, as one preservice teacher suggested,

I think this course was a real look at what adapting to change looks like and we were a big part of it. It really taught me how to make the most out of situations that I have no control over. I think it also highlighted the importance of having connections and asking for help when necessary.

Additionally, other respondents stressed that the course was a positive experience in collaboration, with one student sharing,

Although we did not get to spend valuable time in the physical classroom with students, this course did help me develop professional skills like collaboration and professional communication. My peers and I were able to bounce ideas off of each other and provide each other with immediate feedback on our work and ideas. This course has prepared me for professional collaboration which is so important to the teaching profession.

While respondents may have been disappointed with having their in-school practicum replaced by an online course, many were able to consider how this sudden shift was reflective of the nature of the teaching profession itself.

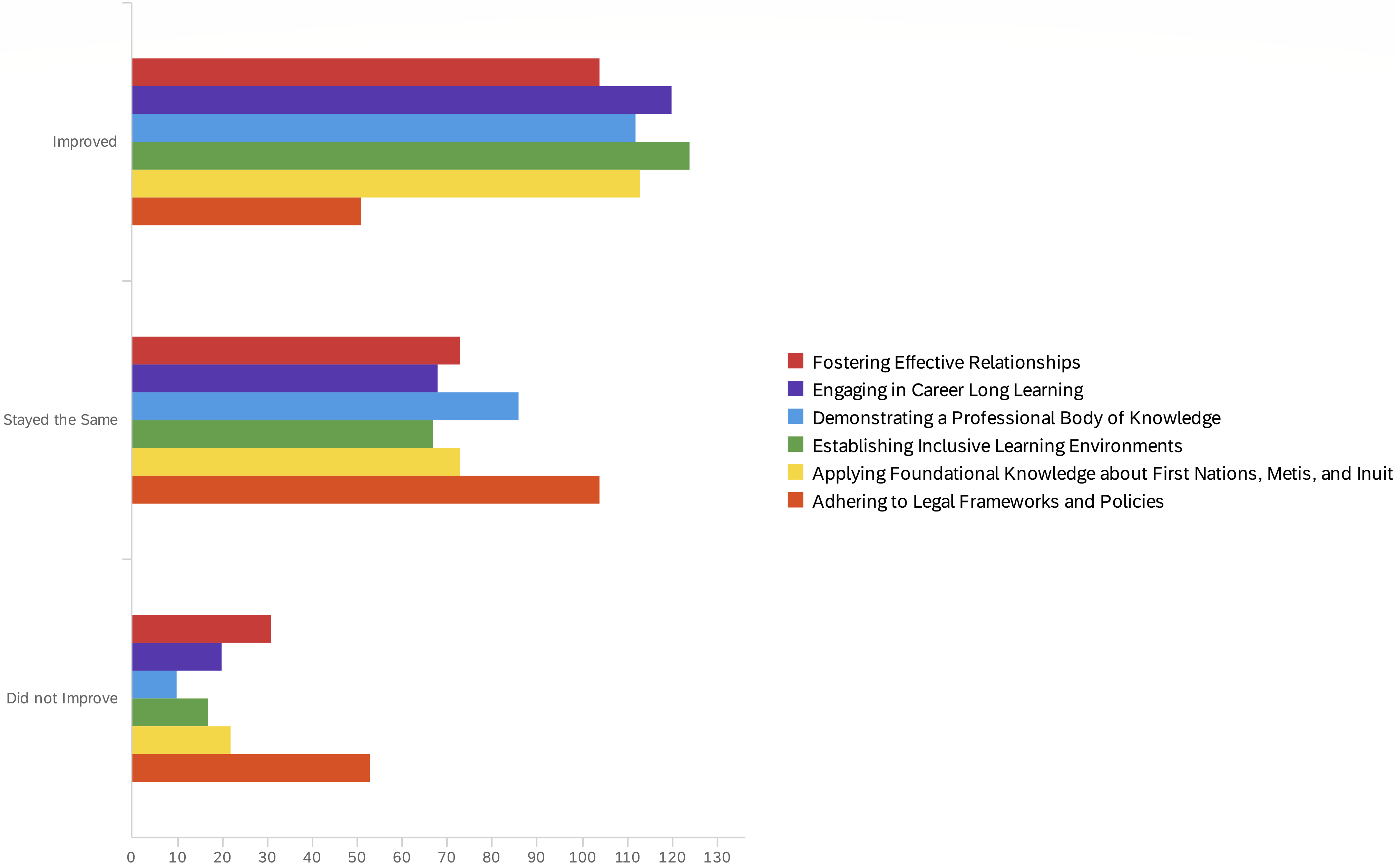

When preservice teachers were asked to consider their learning as it related to the TQS (Alberta Education, 2018), over 50% indicated that they felt more competent in all six of the competencies in the standard with 54% indicating they felt more competent with competency 4 (establishing inclusive learning environments) (Figure 3). Fifty-three percent indicated they felt more competent with competency 2 (engaging in career-long learning) and 50% indicated they had increased confidence with competency 5 (applying foundational knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples).

FIG. 3: Preservice teacher growth within the teaching quality standard

5.5 Suggestions for Improving the Course

In response to the question regarding how the course could be improved, the most frequent suggestion was to include more lesson planning, with 13% of respondents indicating a desire to do more lesson planning. During the course, preservice teachers were asked to submit one full lesson plan, and after receiving feedback from their peers they were asked to submit two revisions to that lesson plan to their instructors. Respondents indicated they would have liked the experience to be more consistent with what they would have experienced if they were in schools, where they would have been submitting one-to-two lesson plans per day. As this preservice teacher explained, “Teachers realistically need to be ready to lesson plan quickly. I think we should have had to write lesson plans every day.” Concurring with the need for more lesson plans, one preservice teacher framed her response this way: “More chances to lesson plan—being able to make one lesson plan and then adapting it is not reflective of the real world.”

The desire to do more teaching was also expressed as a way in which the course could be improved with 9% of responses indicating the course would have been improved if there were more opportunities to teach. Preservice teachers in the course had at least two opportunities to deliver lessons to their small groups and one more opportunity to deliver a lesson to the whole class. Respondents suggested the course should be restructured to include less readings and discussion posts in favor of more teaching time. One preservice teacher stated, “More teaching time, and significantly less readings.” Respondents indicated that the course could be improved by having teaching time more accurately reflect what would have occurred with an in-school practicum:

Provide more opportunities for teaching. Perhaps have students develop a unit plan and teach one micro-lesson to their group per week (this would be closer to the 30% teaching load we were expected to have during Field II). D2L discussion posts were not overly beneficial.

Likewise, another respondent reinforced the desire for more teaching time by stating, “The only thing I would have liked is to have had more opportunities to deliver lessons or longer lessons to our peers.”

Respondents also pointed to the need for more explicit instruction on digital instructional tools and online pedagogy. One respondent suggested “having more knowledge of online teaching resources would be helpful for everyone planning lessons. I spent so much time researching ways online teaching resources. It was overwhelming at times.” Still another shared, “I would suggest a possible segment about how to effectively teach in an online classroom environment so we as students don't just experience it but are able to know how we as future educators can effectively teach online.”

Although schools were not yet ready to begin online learning at the time of the course, 5% of respondents suggested the course would have been improved by providing opportunities to teach K–12 students. Preservice teachers were anxious to interact with K–12 students even if that interaction occurred in an online environment. One respondent shared,

If something like this pandemic were to continue or occur again I think it would be very beneficial if there was a way for us to be able to do some online teaching and lesson delivery with real students in K–12 who are still doing online courses.

Still another echoed that comment, stating, “Allow us to teach actual students online—create lessons and units, assess them.” While the course was successful in shifting perceptions of online education for the majority of the respondents, in the absence of K–12 students, it was unable to replace the experience of an in-school practicum.

6. DISCUSSION

At the time of the course, it was unclear whether schools would begin offering online courses to K–12 students and when they would be accepting preservice teachers into the classroom to complete practicums. Moving the practicum online is contrary to the in-school experiences expected of a practicum, and for many educators doing so during the pandemic was a test of their beliefs about teacher preparation (Kidd & Murray, 2020). With the closure of schools and the halt of traditional practicum experiences, post-secondary institutions were faced with a “curriculum” and “pedagogical vacuum” for student learning (Kidd & Murray, 2020, p. 547). When post-secondary education shifted to online, many faculty members experienced a steep learning curve (Van Nuland et al., 2020) as they redesigned F2F courses while simultaneously learning new technology to deliver these courses. Faculty members were not alone in experiencing a learning curve, and while preservice teachers are viewed as digital natives, Prensky (2001) has reminded us that they often lack the skills, motivation, and competencies to effectively use educational technology in an online environment.

The pandemic practicum described in this article was designed after an examination of the course description used the previous year and consideration of the areas of growth indicated by previous preservice teachers to instructors. Those two areas were differentiation and the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives into their teaching. Based on this knowledge, the course was designed to fulfill several gaps left by the pedagogical vacuum that developed when practicums in schools were canceled. The course provided an opportunity for the preservice teachers enrolled to continue in their program without having to extend the amount of time until degree completion. It provided students with the opportunity to complete practicum weeks required for provincial licensing requirements, in a time of uncertainty. Finally, by continuing learning, the course offered some sense of stability during an uncertain period of chaos, panic, worry, apprehension, and insecurity about the pandemic and how long it would last (Kidd & Murray, 2020). Continuing the learning provided preservice teachers with the opportunity to engage in discussions with their instructors and peers during a time that for many felt very isolating (Metcalfe, 2020).

In designing the course, the researchers drew upon the 22 instructors of the course, to gather feedback on the course design on a weekly basis (Wenger et al., 2002). The feedback from instructors was supportive of the course design, with many offering suggestions and resources for the week ahead. Several instructors added additional synchronous sessions to their course delivery. Those instructors used the additional synchronous sessions to provide individualized feedback to preservice teachers on their lesson plan delivery. In designing the course, the authors limited the number of synchronous sessions to five in an attempt to decrease student and instructor stress in what already was a time of uncertainty.

For the majority of preservice teachers who responded to the pandemic practicum survey, the experience shifted their perspectives about online learning in a positive direction. Preservice teachers expressed appreciation for the variety of teaching strategies and online technology in the course. At the same time, there was a very real sense of disappointment among preservice teachers, with the majority indicating they were very dismayed when they learned that their in-school practicum had been canceled and was being replaced with an online version. It is unclear whether respondents understood that because schools were closed and students were not yet enrolled in online learning, the option of teaching K–12 students online was not available.

Respondents indicated that through the course they had learned how to teach online with much of the learning occurring through peer interaction. In observing their peers' teaching, preservice teachers began to envision new possibilities for their own lessons and developed a greater awareness of the strategies available for their own lessons. However, for many of the respondents, the course fell short of replicating the practical experiences that they would have had in an in-school practicum. As Van Nuland et al. (2020) reminded us, during the practicum, student teachers want to learn from their partner teachers and connect with their K–12 students. There are aspects of the practicum the course was not able to simulate, including responding to spontaneous problems, making on-the-spot decisions, and providing opportunities to manage the classroom (Smith & Lev-Ari, 2005).

Since the course was deliberately designed to address the Alberta TQS (Alberta Education, 2018), the authors provided opportunities for preservice teachers to engage with the two areas preservice teachers often struggle with, namely, differentiation and the integration of Indigenous perspectives. When students were asked to identify which of the competencies they believed they learned the most about, they indicated they learned the most about inclusion and differentiation. Following differentiation and inclusion, respondents indicated the competency they had learned the most about was career-long learning. This was a surprising outcome since it indicates that preservice teachers were able to view the course as a learning experience that was part of a career that would necessitate life-long learning. For many respondents, the course was reflective of a teacher's duty to be flexible and open to ongoing learning.

When asked to consider how the course could be improved, respondents indicated they would have liked more opportunities to lesson plan and teach to their peers. While preservice teachers had opportunities to teach in groups and to the whole class, they indicated they would have preferred if the course had more closely replicated the requirement they would have had to meet if they were completing an in-school practicum. If the practicum had taken place in a school, preservice teachers would have been responsible for designing and teaching at least one lesson per day. The requirement was decreased for the online practicum in order to minimize preservice teacher stress levels and to allow instructors to provide feedback on the 40 lessons they received. It is clear from the findings that preservice teachers would have preferred more synchronous sessions in order to increase the amount of teaching time.

Preservice teachers pointed out that while they had experienced teaching and learning through the completion of the pandemic practicum course, they would have appreciated more direction on the pedagogy and use of educational technology to instruct K–12 students in an online environment. This finding alerted the authors to the importance of examining the concept of digital instructional literacy (Burns et. al., 2020) for preservice teachers. The authors have begun to explore the concept of digital literacy, which they define as “educators' confidence, motivation and competence in using educational technology to instruct students in online environments” (Burns et al., 2020, p. 15).

In examining perceptions of the pandemic practicum, this study provided the authors with insights that extended beyond addressing the pedological gaps created by the absence of in-school practicum opportunities. The data gathered informed future online course design, and in doing so enhanced student learning, which as McKinney and Jarvis (2009) pointed out is essential to the SoTL.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Although the innovation of the newly designed online practicum course was able to shift preservice teachers' perspectives of online learning in a positive direction, it was unable to replicate some of the more spontaneous learning that occurs in the classroom. In the months that followed this course, Alberta's schools offered an online education option for K–12 students. The preservice teachers involved in this study were partnered with mentor teachers and were able to teach in the classroom for at least a portion of their next two practicum experiences. The continued spread of the COVID-19 virus during the 2020–2021 school year meant that the preservice teachers who participated in the pandemic practicum experienced additional theory courses being moved online as well as portions of their subsequent practicum courses. As a result, the preservice teachers in this course completed their final two practicums through a combination of in-class and online delivery.

From a SoTL lens, this study provided the researchers with information that helped to inform future course design. Building upon the lessons learned from this study, the authors made design changes to the two practicums that followed the pandemic practicum. The 2020–2021 practicums that followed were designed to provide a more gradual introduction to teaching responsibilities, thereby providing preservice teachers with more opportunities to observe and assist prior to assuming teaching responsibilities. As a result of this study, preservice teachers who were required to isolate because of exposure to the virus were provided with the opportunity to switch to an online practicum, an option never provided before the pandemic. When 45 preservice teachers were required to self-isolate during a practicum in the fall of 2020, they were able to complete their practicums in online settings. Prior to this adaptation, preservice teachers who missed their in-school practicum were required to drop out or delay the completion of their program. The authors were able to provide preservice teachers with the option of completing a practicum with a mentor teacher in a virtual classroom or provide remote assistance to the F2F classroom. This change recognized the value of teaching and learning in an online environment, and in the future may provide alternatives for preservice teachers unable to complete an in-person practicum or who wish to teach in online or virtual classrooms.

Further study on the role that practicums plays in developing the digital instructional literacy of preservice teachers and university instructors has been initiated. While the survey data indicated that preservice teachers' perceptions of online instruction improved as a result of their experience in the pandemic practicum, more nuanced data are required to understand why that shift occurred. Additionally, more research needs to focus on how to best incorporate the key competencies of digital pedagogies into preservice teacher education after the pandemic. As school systems integrate more online learning into K–12 classrooms, teacher education programs need to build the digital instructional literacy of preservice teachers to align with that shift.

REFERENCES

Alberta Education. (2018). Teaching quality standard. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/4596e0e5-bcad-4e93-a1fb-dad8e2b800d6/resource/75e96af5-8fad-4807-b99a-f12e26d15d9f/download/edc-alberta-education-teaching-quality-standard-2018-01-17.pdf

Armstrong, K., & Mulvihill, T. M. (2007). Undergraduate students' perceptions of online learning. In R. C. Young (Ed.), Proceedings of the 26th Annual Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, Community and Extension Education, 7–12. https://www.academia.edu/29754892/Undergraduate_Students_Perceptions_of_Online_Learning?email_work_card=view-paper

Burns, A., Danyluk, P., Kapoyannis, T., & Kendrick, A. (2020). Leading the pandemic practicum: One teacher education response to the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of E-Learning and Education, 35(2), 1–25. www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1173

Chiasson, K., Terras, K., & Smart, K. (2015). Perceptions of moving a face-to-face course to online instruction. Journal of College Teaching & Learning 12(4), 231–240.

Compton, L., Davis, N., & Correia, A.-P. (2010). Pre-service teachers' preconceptions, misconceptions, and concerns about virtual schooling. Distance Education 31(1), 37–54. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01587911003725006

Creswell, J. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Strengthening clinical preparation: The Holy Grail of teacher education. Peabody Journal of Education 89(4), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2014.939009

Doreleyers, A., & Knighton, T. (2020, May 14). COVID-19 pandemic: Academic impacts on postsecondary students in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00015-eng.htm

Felten, P. (2013). Principles of good practice in SoTL. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.1.1.121

Fish, W. W., & Gill P. B. (2009). Perceptions of online instruction. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 8(1), Article 6. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED503903

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Hutchings, P., & Shulman, L. S. (1999). The scholarship of teaching: New elaborations, new developments. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 31(5), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091389909604218

Hutchings, P., Borin, P., Keesing-Styles, L., Martin, L., Michael, R., Scharff, L., Simkins, S., & Ismail, A. (2013). The scholarship of teaching and learning in an age of accountability: Building bridges. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 1(2), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.1.2.35

Jackson, B. L., & Jones, W. M. (2019). Where the rubber meets the road: Exploring the perceptions of in-service teachers in a virtual field experience. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2018.1530622

Jones, M., & Ryan, J. (2014). Learning in the practicum: Engaging pre-service teachers in reflective practice in the online space. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.892058

Kennedy, K., & Archambault, L. (2011). The current state of field experiences in K–12 online learning programs in the U.S. In M. Koehler & P. Mishra (Eds.), Proceedings of SITE 2011 – Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, 3454–3461. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Kidd, W., & Murray, J. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education in England: how teacher educators moved practicum learning online. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 542–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1820480

McKinney, K., & Jarvis, P. (2009). Beyond lines on the CV: Faculty applications of their scholarship of teaching and learning research. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030107

Metcalfe, A. S. (2020). Visualizing the COVID-19 pandemic response in Canadian higher education: An extended photo essay. Studies in Higher Education, 46(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1843151

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Ralph, E., Walker, K., & Wimmer, R. (2009). Deficiencies in the practicum phase of field-based education: Students' views. Northwest Journal of Educational Practices, 7(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.15760/nwjte.2009.7.1.8

Schulz, R. (2005). The practicum: More than practice. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de L'Éducation, 28(1/2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602158

Smith, K. & Lev-Ari, L. (2005). The place of the practicum in pre-service teacher education: The voices of the students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500286333

Trigwell, K. (2013). Evidence of the impact of scholarship of teaching and learning purposes. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 1(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.1.1.95

Van Nuland, S., Mandzuk, D., Tucker Petrick, K., & Cooper, T. (2020). COVID-19 and its effects on teacher education in Ontario: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1803050

Wall, K. (2020, May 25). COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on the work placements of postsecondary students in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00022-eng.htm

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School.

White S., & Forgasz, R. (2016). The practicum: The place of experience?. In J. Loughran & M. Hamilton (Eds.), International Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 231–266). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_6

Wilkens, C., Eckdahl, K., Morone, M., Cook, V., Giblin, T., & Coon, J. (2015). Communication, community, and discussion: Pre-service teachers in virtual school field experience. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 43(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.2190/ET.43.2.c

Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(5), 633–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2014.11777343

-

Kendrick Astrid, Starting from a Place of Academic Integrity: Building Trust with Online Students, in Ethics and Integrity in Teacher Education, 3, 2022 Crossref (open in a new tab)

Comments

Show All Comments