AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC REFLECTIONS ON TEACHING AND LEARNING PHYSIOLOGY ONLINE: PERSPECTIVES FROM A PHYSICAL THERAPY INSTRUCTOR AND STUDENT IN A POST-PANDEMIC CURRICULUM

Physiology has been traditionally taught to physical therapy (PT) students from the perspective of medical physiology. However, since physical therapists have established themselves as movement experts in healthcare, it is increasingly appropriate for PT students to learn physiology through the lens of human movement. During the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the transition to emergency remote education provided a unique opportunity to reimagine how physiology could be taught in a virtual environment. This article reflects on the creation and evolution of a movement-centered, online-friendly physiology course designed specifically for PT students. The course's structure, assessment strategies, and virtual delivery innovations are discussed from both faculty and student perspectives. This dual reflection highlights how a novel instructional lens, shaped by online delivery constraints, fostered meaningful learning outcomes that extended beyond the virtual classroom.

KEY WORDS: physiology, pathophysiology, physical therapy, emergency remote education, human movement, verbal practical exams, autoethnographic narrative

1. THE INSTRUCTOR'S REFLECTION

1.1 Developing a Movement-Centered Lens for Online Physiology Instruction in Physical Therapy Education

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated numerous changes in instructional delivery, including the rapid transition to emergency remote education (Bozkurt et al., 2020; Hodges et al., 2020). For physical therapy (PT) education, which traditionally relies on in-person engagement, this shift raised new challenges and opportunities. During this period, I was asked to design and deliver a physiology and pathophysiology course for first-year students in the Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) program, in an entirely online format. The virtual teaching environment and perceived pandemic stress among students (Anderson and Dutton, 2022), forced me to think of teaching physiology to PT students through a lens that would be more engaging, relatable, and focused on the highest priority content pertinent to serving as movement experts—out of these constraints was born the idea of movement-centered physiology instruction.

At the time of developing the course, I was navigating both professional uncertainty—maintaining my existing muscle biology research program while adapting it to COVID-19-related priorities (Begam et al., 2020; Roche and Roche, 2020)—and personal grief following the passing of my father. Thus, I experienced frequent anxious thoughts and persistent self-doubt. Working with a counselor during this period helped me recognize how my anxiety stemmed from a deep sense of responsibility—not just to deliver content, but to do justice to the profession I love (i.e., PT) and the physiological function I consider sacred (i.e., human movement). This realization reframed anxiety as a sign of purpose. Once I embraced that, designing and teaching a physiology course through the lens of human movement became a source of inspiration rather than apprehension (Irving et al., 2017; Sutin et al., 2022). Purpose did not eliminate the challenge, but it gave the challenge meaning, which I found deeply motivating. After exploring various approaches, my therapist and I gravitated toward the dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) framework—an approach originally developed for borderline personality disorder, but now recognized for its broader applications in enhancing cognition and productivity. DBT's “wise mind” strategies integrate the emotional and rational (reasonable) minds, fostering decisions that are informed by both emotion and reason (Chapman, 2006; Vijayapriya and Tamarana, 2023).

Rather than teaching physiology as a generic course on various physiological systems, I reframed the course around the central concept of movement being the integrative goal of all physiological systems. This yielded four instructional blocks: Moving the Body (muscle and nerve), Moving Materials around the Body (cardiovascular and pulmonary systems), Fueling Movement (cellular respiration), and Decoding the Genetics of Human Movement (gene expression and protein synthesis) (Figure 1). These blocks provided a unifying structure, which not only helped students contextualize information, but also mirrored clinical reasoning used in PT.

FIG. 1: Summary of the four blocks covering the physiology and pathophysiology of human movement for Doctor of Physical Therapy students. Created in https://www.biorender.com/

1.2 Mentorship

Throughout the process of developing and optimizing this course, I drew support from academic mentors, most notably Prof. Steven Fink, whose lecture notes, videos, and feedback informed my approach. Prof. Fink's mentorship helped affirm that complex topics, such as cellular respiration and genetics, could be taught clearly and confidently when framed around the concept of purposeful movement. Ongoing support from Wayne State University's Office of Teaching and Learning also contributed to the sustainability of the model.

1.3 Online Course Delivery Details

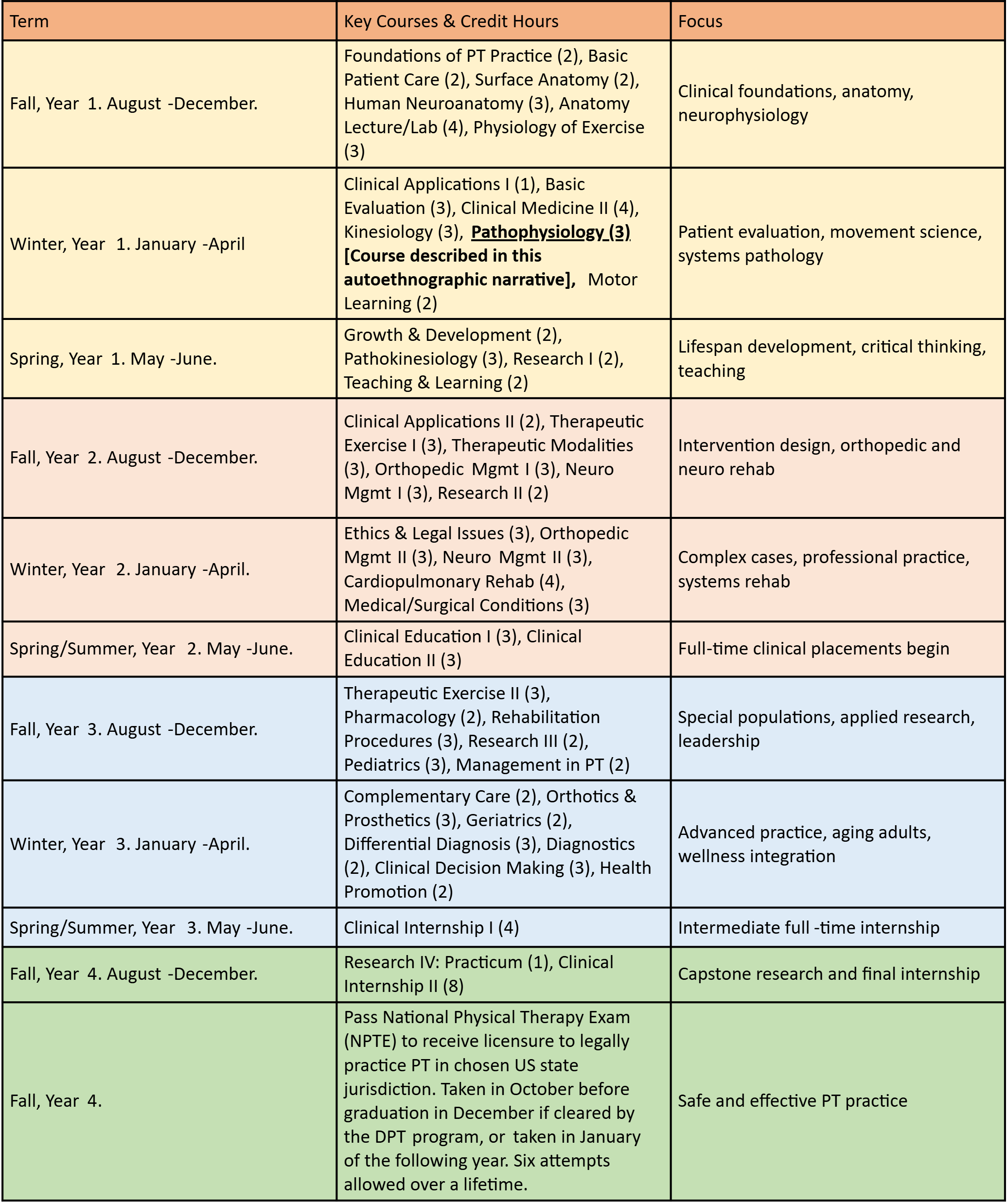

When this course was delivered fully online (2021–2024), instruction was through the Zoom online learning platform (Zoom Communications, Inc., San Jose) (Carmi, 2024; Kikuchi, 2025). Zoom was and continues to be embedded within Wayne State University's default web-based learning management system (LMS), CANVAS (Instructure Holdings, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) (Al-Ataby, 2021). The first cohort that took the course consisted of 36 students who were enrolled in Wayne State University's DPT program, which was and currently is three years and four months in duration (curriculum overview in Figure 2). Please refer to the university's PT program website for most current information.

FIG. 2: Overview of the DPT program curriculum at Wayne State University. Created in https://www.biorender.com/

Since our DPT program resumed some hands-on instruction as soon as it was permitted by federal, state, and university policies, all students chose housing that was within daily commuting distance from campus. The course was part of the second semester of the first-year DPT curriculum—the timing of this course in the DPT curriculum is to equip students with foundational knowledge in physiology and pathophysiology before they start clinical content (e.g., PT for orthopedic, general medical and surgical, neurological, and cardiopulmonary conditions, PT modalities, etc.) and clinical rotations. The class met on Friday afternoons from 1 to 4 PM—a detail I chose to mention, because, when the first cohort of students that took this course graduated, they jovially shared how they had dreaded attending a three-hour Zoom session on Friday afternoons—but, over time, began to look forward to this class—mainly because of the movement-centered physiology lens and its relevance to PT practice and health education. This type of live, web-based course delivery was designated as “synchronous online” (Hung et al., 2024) in the syllabus, according to university policies. All synchronous online sessions (i.e., all classes) were recorded with Zoom's “Record to Cloud” option and posted in the Canvas site for the course. After each synchronous online session concluded, the recording was stopped, and “office hours” began.

Office hours are designated times during which students can meet with instructors for additional discussion (Benaduce and Brinn, 2024). The discussions during office hours for the course were mostly on course content or business matters related to the course [e.g., exam rubrics, study guides, exam roster (the order in which students would take a practical exam), scheduling conflicts, etc.]. Typically, about five to eight students would stay on for office hours. On occasions, during office hours, students would share interesting anecdotes from their experiences as volunteers in PT settings, in connection to what they were learning in the course—some of these anecdotes were incorporated into clinical case scenarios, which were discussed later with the entire class. In addition to formal office hours after class, students were invited to reach out via email to set up appointments to meet as needed. As indicated in Figure 1, after synchronous sessions within a block were completed, there was a culminating verbal practical exam for that block, which had to be passed to pass the course.

1.4 Verbal Practical Exams

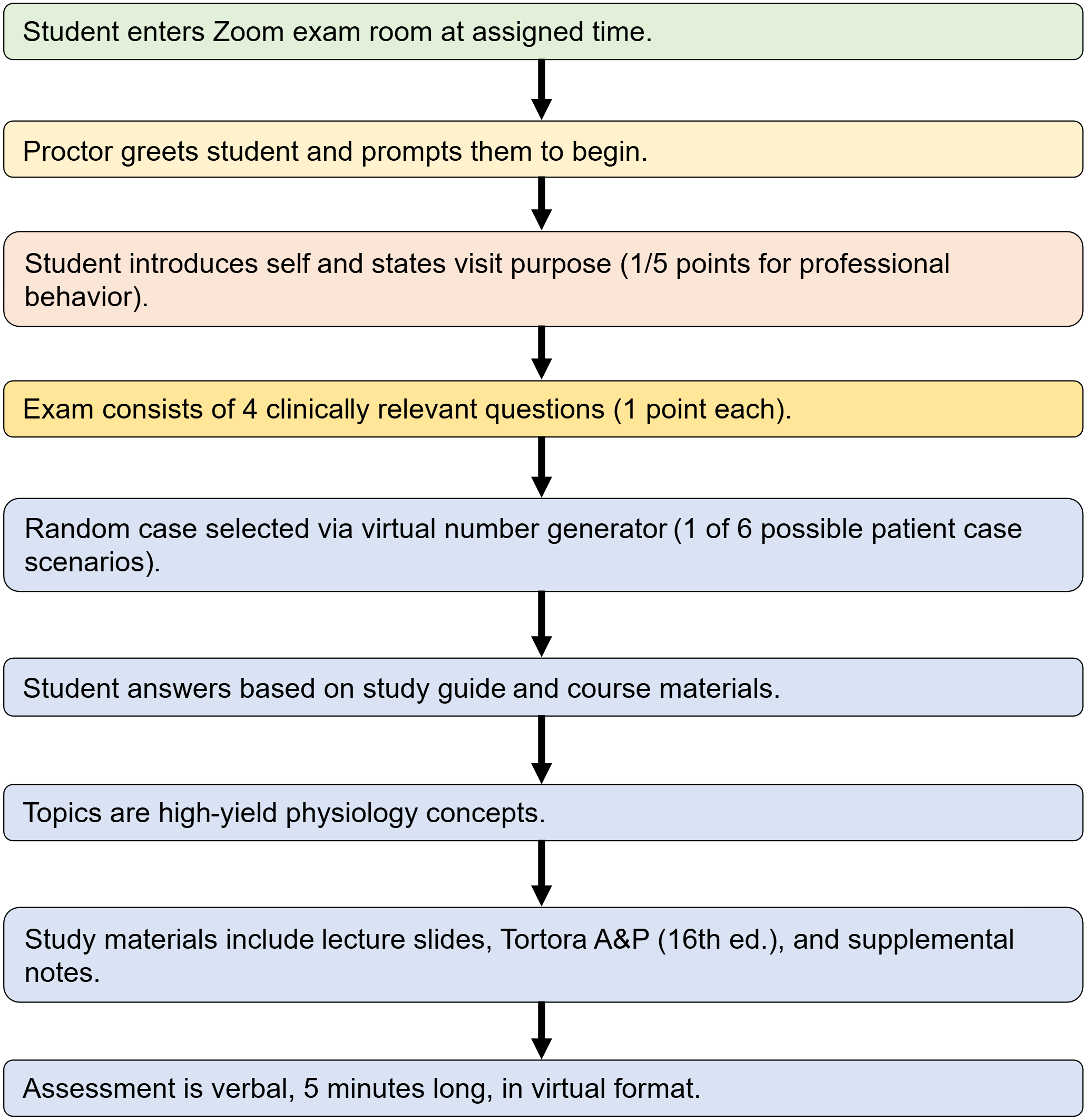

To ensure that students had sufficient knowledge competence in physiology and were able to apply their physiology knowledge appropriately to clinical contexts, verbal practical exams were implemented for each block (Figure 3). These exams were conducted on Zoom, where students were given a clinical case scenario, based on which they had to answer specific questions.

FIG. 3: Workflow for verbal practical exams. Created in https://www.biorender.com/

An exam roster (order in which students would take the exam) was posted in advance. Up to ten students were allowed in the Zoom waiting room. Students entered the actual Zoom exam room at their designated time slot. The examiner/proctor greeted the student and asked them to start. The student introduced themselves and conveyed the purpose of their visit (e.g., “My name is _____________, I am a student PT. I would please like to discuss the medical information of a patient who has been referred to PT.”). The student received one out of five total exam points, just for the introduction, to reward professional behavior. The introduction was not only a way to emphasize the importance of professional behavior, but it was also meant to ease students into the exam, which for most individuals was in an unaccustomed format—verbal demonstration of knowledge competence in physiology, in a virtual environment, within a five-minute time window.

Following the introduction, four questions pertinent to the virtual patient's clinical condition were asked and each question was valued at one point. Knowledge competence was assessed on certain high-priority (what I call “high-yield”) topics that were highlighted in class. At the end of the exam, students were told what their score was and if they had to retake the exam. Retakes (second attempts) were individually scheduled and conducted the same way as the first attempt. However, on a second attempt, the maximum score was capped at the minimum passing score of four out of five, which was consistent with our DPT program's policies for practical exam retakes. On occasions, students were asked to attend remedial learning sessions with the instructor based on their performance on the first attempt (e.g., if there was an indication that there were knowledge gaps in physiological organization from organismic down to the molecular level, i.e., being able to distinguish what happens in disease states at a whole body level and how that is related to pathophysiological processes at a molecular level).

For each practical exam, students were given a study guide that listed six different patient case scenarios with a set of four questions for each scenario. Students were directed on where to find the necessary information in the lecture slides/notes, the course textbook (Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, 16th Ed., by Gerard J. Tortora and Bryan H. Derrickson), and notes and summaries to supplement the study guide. The specific patient case scenario for each student was chosen by a virtual random number generator during the exam (choice from one to six).

As part of the syllabus and practical exam rubric, students were informed that the practical exams were open book, which meant that they could refer to their notes. However, students were advised that questions had to be answered in a conversational style and that, due to the five-minute time window, there would not be enough time to search for answers during exams.

The four verbal practical exams were equally weighted and contributed to 20% of the course grade. Take-home quizzes (one quiz after each synchronous session, open book, two attempts per quiz, not timed, formative and summative assessment) contributed to 40% of the course grade. In-class quizzes (one quiz at the beginning of each synchronous session, open book, ten minutes, one attempt) contributed to 20% of the course grade. A cumulative final written exam (open book, timed, 60 questions in 120 minutes) contributed to 20% of the course grade.

The virtual format for verbal practical exams was not only logistically feasible during remote instruction, but also uniquely effective. It encouraged knowledge recall and integration, cultivated communication skills, and, most importantly, reinforced the value of physiology in clinical practice. The exams demonstrated that assessment in an online setting could move beyond multiple-choice tests to support deeper conceptual engagement and clinical reasoning. Study guides, grading rubrics, and exemplar answers were posted online, consistent with the principles of transparency in learning and teaching (Winkelmes, 2013).

Student feedback consistently reflected appreciation for this format. Students reported feeling more prepared to explain physiological principles to patients and peers alike. The structure also provided the opportunity for individualized feedback, and reinforced purpose-driven learning, which is consistent with educational research on motivation (Yeager et al., 2014). After the first iteration of the course, in the qualitative feedback received through the university's formal student evaluation of teaching survey, a student wrote: “Absolutely exceptional professor. Please continue to do what you are doing for future cohorts. You must keep the verbal practical examinations for this class. Testing one's ability to verbally explain how the body functions and how it is dysfunctional is the perfect way to assess if true learning has occurred.” Another student wrote: “I really enjoyed the format of this class. The virtual exams in this class forced us to really understand the content in a way that we can talk about it, rather than learning to answer a multiple choice question. I hope future students are able to learn as much as I did from this class.”

1.5 Sustainability of the Movement-Centered Physiology Instruction Model

Having just completed the fifth iteration of the course (the first in-person version), the course continues to evolve. Although originally designed for remote delivery, several online components, such as verbal practical exams and asynchronous review materials remain in use despite transitioning to in-person instruction. These online components have proven effective in supporting diverse learning needs and accommodating flexible instruction. Feedback from multiple cohorts has been used to refine content and assessments. Student success on PT license exams and in clinical placements suggests that the movement-centered approach, augmented by online modalities, resonates beyond the virtual classroom (highlighted in the student reflection that follows). The framework that involves movement-centered physiology instruction with the flexibility to be delivered fully or partially online could serve as a curricular model for integrating physiology and clinical reasoning in PT education across varied instructional settings.

1.6 Tips for the Online Educator

The biggest lesson I have learned from teaching movement physiology in an online environment is that verbal exams are better indicators of knowledge competence than multiple-choice written exams. Additionally, in my experience, the gravity of having to pass verbal practical exams to pass the course encouraged students to be more attentive and focused when high-yield information pertinent to practical exams was emphasized in class. Emphasis on verbal testing also appears to be gaining support to counter threats to learning and academic integrity that might arise from the abuse of artificial intelligence programs, which could be an even greater concern in online instruction (Fenton, 2025). Having a small class size of 36 students was certainly a plus when it came to verbal practical exams. Feasibility would be a concern with large class sizes.

Another important lesson that I learned was that focusing on a few high-yield topics and ensuring that students gained a thorough understanding of those topics was effective in helping students extrapolate that information deductively to other topics. In the past, for my other courses, I used to try to cover a much larger set of topics per lecture/lab. However, online teaching has helped me learn how to prioritize the highest-yield content first, and then use that mastered content to understand other important related topics.

Finally, I have learned that students do learn how to cope with the demands of rigorous verbal practical exams. When they learn to successfully navigate high-stakes, high-stress verbal practical exams, they usually start doing better in other courses in the DPT program. A former student once shared how the physiology verbal practical exams had made that student stronger and more confident in other PT-technique-related practical exams. Similar sentiments are expressed in the student reflection that follows.

2. THE STUDENT'S REFLECTION

2.1 The Background

If you understand the basics of a subject, there is very little you will need to memorize (Bransford et al., 2000; Roth, 2013).

I think Dr. Roche (who goes by “Roche”) had this at the forefront of his mind when he designed a physiology course that set me and my student cohort up for future success. I took Roche's physiology and pathophysiology of human movement course (“pathophysiology”) as a first-year student in Wayne State University's Doctor of Physical Therapy program. We learned about human movement from the molecular level up through the level of organ systems. In our other courses, we were busy learning different techniques required to be physical therapists, but pathophysiology taught us the basics of how the body works to make safe, purposeful, and enjoyable movement a possibility and priority.

2.2 Practical Exams

The course was unusual in that we were tested via verbal practical exams. I found a few distinct benefits to this setup. The first was that it helped prepare me to speak on the subject of pathophysiology with my patients, which for me was the most practical and direct application of the course. It also forced me to adapt my study strategies, accommodate change, and be able to think on the fly. PT school requires a major shift in learning strategies from those that help us find success as undergraduates (i.e., bachelor's degree students), to those that will help us with long-term retention and practical application. Throughout my DPT training, I did quite a bit of tutoring and noticed that the students who struggled most seemed to be the ones who had the most difficulty with this change. Preparing for verbal exams in my first year helped me change my study strategies from memorization to understanding, which served me well through the rest of the program, during my National Physical Therapy Exam (NPTE) preparation, and as a practicing therapist. The NPTE is the U.S. PT license exam, which must be passed close to or after graduation to obtain licensure in the chosen U.S. state jurisdiction—the maximum score is 800 and the minimum passing score is 600. The verbal practical exams also helped train me to keep my composure when asked challenging questions, which was useful during practical exams in other courses, as well as while working with patients.

2.3 Emphasis on Foundational Concepts through the Lens of Movement

For me, pathophysiology provided a set of building blocks upon which I built my knowledge of other conditions as I went through the DPT program. I understood spinal cord injuries because I understood the physiology of the spinal cord. I did not have to memorize various cardiopulmonary conditions because I understood the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems and how dysfunction in various areas could affect them. When it was time to review these concepts before taking the NPTE, I could refresh my memory by thinking of the pathophysiology content we learned and using that to reason through the different diagnoses and treatments. Roche helped us revisit many of these concepts through his Pathokinesiology and Pharmacology courses later in the curriculum.

2.4 Simplifying the Complex Based on the Ideas of Moving the Body, Moving Materials around the Body, Fueling Movement, and Decoding the Genetics of Movement

Roche did an admirable job of sorting through the complexities of molecular biology, genetics, and physiology to pull out the most important nuggets that would help us later on. We do not need to know the nitty gritty details of cellular biology to be good therapists, but we do need to know enough to recognize and understand the pathologies that affect the individuals that we treat. Even now, four years after taking pathophysiology, and working as a practicing therapist for over a year, I mentally refer to what we learned in pathophysiology when faced with a challenging patient presentation or a new diagnosis. When I encounter a problem that does not yet have enough literature around it, I can use foundational knowledge and treat safely and effectively.

2.5 Health Education

As much as this course helped me understand the pathophysiology of human movement, it also helped me to provide education to my patients. Understanding pathophysiology helps me to educate my patients confidently, which builds trust and rapport. While every patient does not need a pathophysiology lecture, the ones who are interested appreciate the depth of education I can provide. In addition to patient education, I also think pathophysiology trained me to be more confident when I interact with fellow healthcare professionals and administrators.

2.6 Closing Remarks

We must understand the basics. We cannot call ourselves experts in human movement if we do not fully understand how movement is accomplished and how it becomes dysfunctional. For me, Roche's pathophysiology course was one of the cornerstones in acquiring, retaining, and applying knowledge on the physiology and pathophysiology of human movement.

2.7 Additional Note on the Student's Reflection

On the NPTE, the student secured a full score of 800/800 and her entire cohort passed on the first attempt (i.e., a 100% first-time pass rate). Typical first-time pass rates may range from 86 to 93% over a ten-year period (Dickson et al., 2020).

DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY

The authors declare that this work has not been published before. An earlier narrative version of the instructor's reflection appeared in 2021 as a blog post for the American Physiological Society's Physiology Education Community of Practice. The current paper presents a significantly revised account, includes a student's reflection, and introduces the refined pedagogical framework that has emerged from subsequent course iterations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During the writing of this paper, Joseph A. Roche was supported by a subcontract from NIH No. R01AR079884-01 (Peter L. Jones PI). The authors express their gratitude to the Physical Therapy Program and the Office of Teaching and Learning at Wayne State University for supporting innovation in teaching and learning. Roche expresses his gratitude to Professor Fink for serving as a physiology teaching mentor and making numerous learning resources available online without cost.

REFERENCES

Al-Ataby, A. (2021). Hybrid learning using canvas LMS. Eur. J. Educ. Pedag., 2(6), 27–33.

Anderson, C. E. P. & Dutton, L. L. (2022). Physical therapy student stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. J. Phys. Ther. Educ., 36(1), 1–7.

Begam, M., Roche, R., Hass, J. J., Basel, C. A., Blackmer, J. M., Konja, J. T. Samojedny, A. L., Collier, A. F., Galen, S. S., and Roche, J. A. (2020). The effects of concentric and eccentric training in murine models of dysferlin-associated muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve, 62(3), 393–403.

Benaduce, A. P. & Brinn, L. (2024). Reenvisioning office hours to increase participation and engagement. J. Coll. Sci. Teach., 53(4), 364–366.

Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., Olcott, Jr., D., Lambert, S., Al-Freih, M., Pete, J., Olcott, D., Rodés, V., Aranciaga, I., Bali, M., Alvarez, A., Roberts, J. J., Pazurek, A., Raffaghelli, J., Panagiotou, N., de Coëtlogon, P., Shahadu, S., Brown, M., Asino, T., Tumwesige, J., Ramírez Reyes, T., Barrios Ipenza, E., Ossiannilsson, E. S. I., Bond, M., Belhamel, K., Irvine, V., Sharma, R., Adam, T,, Janssen, B., Sklyarova, T., Olcott, N., Ambrosino, A., Lazou, C., Mocquet, B., Mano, M., & Paskevicius, M. (2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ., 15(1), 1–126.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn, Vol. 11, National academy press, Washington, DC.

Carmi, G. (2024). E-learning using Zoom: A study of students? Attitude and learning effectiveness in higher education. Heliyon, 10(11), e30229.

Chapman, A. L. (2006). Dialectical behavior therapy: Current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 3(9), 62–68.

Dickson, T., Taylor, B., & Zafereo, J. (2020). Characteristics of professional physical therapist faculty and doctor of physical therapy programs, 2008–2017: Influences on graduation rates and first-time national physical therapy examination pass rates. Phys. Ther., 100(11), 1930–1947.

Fenton, A. (2025). Reconsidering the use of oral exams and assessments: An old way to move into a new future. Educ. Res., 54(7), 430–436.

Fink, S. (2025). Links to physiology. Retrieved February 10, 2025 from http://professorfink.hstn.me/PHYSIOLOGY.html

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Rev., 27, 1–12.

Hung, C. T., Wu, S. E., Chen, Y. H., Soong, C. Y., Chiang, C. P., & Wang, W. M. (2024). The evaluation of synchronous and asynchronous online learning: Student experience, learning outcomes, and cognitive load. BMC Med. Educ., 24(1), 326.

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: Systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev., 85(4), 403–437.

Kikuchi, K. (2025). Restructuring physical therapy education after COVID-19: A narrative review on the global perspectives and the emerging role of hybrid learning models. Cureus, 17(7), e88034.

Roche, J. A. & Roche, R. (2020). A hypothesized role for dysregulated bradykinin signaling in COVID-19 respiratory complications. FASEB J., 34(6), 7265–7269.

Roth, K. J. (2013). Developing meaningful conceptual understanding in science, Ch. 4, Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction, Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, UK, 139–175.

Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2022). Sense of purpose in life and motivation, barriers, and engagement in physical activity and sedentary behavior: Test of a mediational model. J. Health Psychol., 27(9), 2068–2078.

Vijayapriya, C. V. & Tamarana, R. (2023). Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy as a transdiagnostic treatment for improving cognitive functions: A systematic review. Res. Psychother., 26(2).

Winkelmes, M. (2013). Transparency in learning and teaching: Faculty and students benefit directly from a shared focus on learning and teaching processes. NEA Higher Educ. Advoc., 30(1), 6–9.

Yeager, D. S., Henderson, M. D., Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., D'Mello, S., Spitzer, B. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 107(4), 559–580.

Comments

Show All Comments