AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY: A PHYSIOTHERAPY STUDENT'S EXPERIENCE OF EMBODIED LEARNING ONLINE DURING THE PANDEMIC

*Address all correspondence to: Laura Blackburn, Glasgow Caledonian Univeristy, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow, G4 0BA, UK, E-mail: lblack207@caledonian.ac.uk

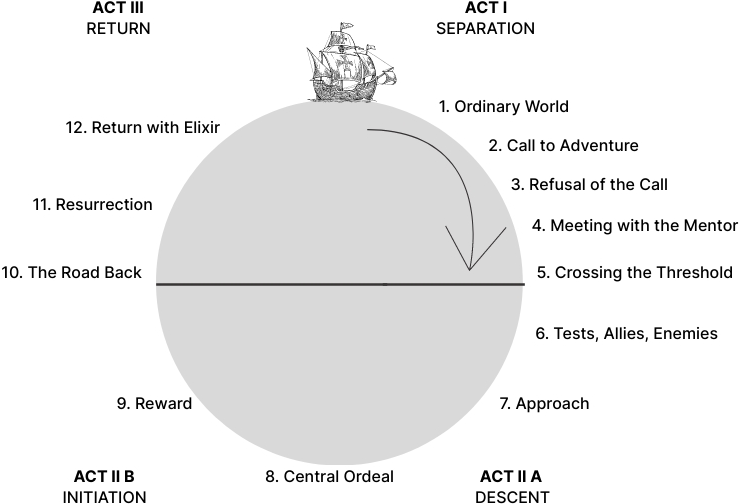

Touch is known to be a key facilitator for embodied learning for physiotherapy students. Through embodied learning, students use their body and touch as tools to deepen their anatomical understandings of different bodies, communicate abstract concepts, and in interacting with others. Hands-on skill development enables the integration of knowledge, skill, and affective domains to create an embodied understanding and body awareness. Pandemic-related restrictions meant many students were unable to attend practical classes face to face. Instead, tutorials transitioned online, taking students and lecturers on a journey never before traveled in the field of physiotherapy. Staff and students, no longer able to use touch for embodied learning, had to find new ways of thinking, being, and doing to achieve this online. This article presents one student's experience of online learning through the three-act structure of the Vogler model of the hero's journey (Vogler, C, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structures for Writers, 25th Anniversary, 4th Ed., Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City, CA, 2020). Vogler offers a 12-stage arc, known to correspond with many Hollywood movies and fiction books. Considering how the different stages relate to the learning experience provided a framework that facilitated the learner's reflection. The first act illustrates the learner's pre-pandemic world, the adaptations to learning due to COVID-19 restrictions, and the online learning adventure. Act 2 provides the path to the midpoint, with allies, enemies, trials, and rewards. The hero's journey concludes with the third act, detailing the gradual return from pandemic restrictions and an appreciation for the new skills developed through online learning. A final section provides three recommendations for the future of online learning.

KEY WORDS: embodied learning, the hero's journey, online learning

1. INTRODUCTION

The human body is the beating heart of the physiotherapy or physical therapy profession. Physiotherapy aims to “develop, maintain, and restore maximum movement and functional ability throughout the lifespan” of individuals and populations (WCPT, 2022). Restoring functional movement is key to physiotherapy rehabilitation as it is central to the meaning of a healthy body (WCPT, 2022). The body can be understood as acquired through interaction with self, others, and the environment (Langaas and Middelthon, 2020).

Students learn about and through bodies (Langaas and Middelthon, 2020), by embodied cognition or learning (Skulmowski and Rey, 2018). Embodied learning involves gesturing in communication and bodily enactment, such as using the body as a tool to explain abstract concepts (Skulmowski and Rey, 2018). Tacit knowing, relevant to human movement, explains the complexity of knowledge and limits of knowledge sharing (Kontos and Naglie, 2009). For example, walking includes a process of forming bodily habits and components of tacit knowing (Gourlay, 2005), often difficult to verbalize. In becoming attuned to others' lived experience of their body, physiotherapy student development often coincides with learning about their own (Sheets-Johnstone, 2002). Knowledge of the human body and its movement creates an attentive, sensitive, and affected body experience (Latour, 2004). Movement often incorporates complex focal and subliminal attention (Polanyi, 1962). Understanding the complexities requires a process of dynamic learning to become affected and have a more embodied body, with ways of knowing specific to physiotherapy (Latour, 2004; Langaas and Middlethon, 2020).

Embodiment offers a lens in which to view a body as a whole person, respecting diversity and fostering an inclusive attitude (Nicholls and Gibson, 2010). Throughout physiotherapy training, students attend to their own, other students', and patients' bodies. Students learn through experimentation and exploration, which enhances bodily awareness and understanding of what is usually tacit knowing or a part of subliminal attention (Langass and Middlethon, 2020). In developing an embodied view, the student not only considers biomechanical and tissue damage, but the wider social and cultural impact of the injury and treatment (Nicholls and Gibson, 2010). Students create a norm for comparison and understanding meaning by learning of a generalized body (Langaas and Middlethon, 2020). Acquiring knowledge through visual and practical lived experience in their body, rather than through biomechanical calculations, allows a sensitizing and dynamic process of learning by doing (Schön, 1987). Touch can be important for developing the knowledge, skills, and behavior necessary for verbal and nonverbal communication, tactile-kinaesthetic knowledge (Sheets-Johnstone, 2002), and bodily-emotional knowledge (Laird and Lacasse, 2014), useful in the process of making meaning and embodied learning (Langaas and Middlethon, 2020).

Practical tutorials and clinical rotations offer valuable time to apply generalized learning, develop clinical reasoning, and an embodied understanding. Students enrolled in a physiotherapy program from March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, experienced disrupted access to hands-on training. Universities faced unprecedented circumstances, leading to campus closures, a rapid transition to online-only learning, with adaption in teaching methods. This paper details the new ways of doing, being, and thinking during online learning for one physiotherapy student enrolled in the Doctor of Physiotherapy (DPT) preregistration program at Glasgow Caledonian University. A student–staff partnership formed the writing approach, with staff facilitating reflection and co-writing sections. The Vogler (2020) model of the hero's journey offers a framework for student reflection, with links made between the hero's journey and that of a learner (Land, 2019).

This paper follows a three-act structure of the hero's journey (see Figure 1). Act 1 begins with the hero from their ordinary world prior to encountering their call to adventure or inciting incident, followed by a refusal of the call, meeting with the mentor, and crossing the threshold. The second act involves four main events, including: (i) tests, allies, enemies; (ii) approach to the inmost cave; (iii) ordeal or midpoint; and (iv) reward. Act 3, the final act, details the hero on the road back, their resurrection or climax, and the return with elixir or denouement.

FIG. 1: Hero's journey, adapted from Vogler (2020), p. 9

2. ACT 1

2.1 Ordinary World

My enrolment in the DPT program might be viewed by some onlookers as unexpected. I never considered physiotherapy to be an option until after I opened a sports massage business. With a psychology undergraduate degree, I planned my postgraduate studies to be focused on evolutionary psychology research. My business became a passion and rerouted my goals toward a new profession. The transition from psychology to physiotherapy cannot be described as simple. It required years of preparation before my application to the DPT program. Even then, I was far from certain of acceptance. I knew of the competitive nature of the course, with some repeating the applicant process for three years before being accepted into a program. Concerns my application might also be declined on the first attempt seemed realistic and highly likely.

Against perceived odds, someone saw potential in my application. My DPT journey began with shared classes with MSc students, completing the preregistration physiotherapy modules. Our education progressed at an accelerated speed and an intensity that often left me breathless with anxiety. All my attention focused on the human body, from my pre-class reading, class content, study time with peers, and the working hours in my business. Unlike my experience in undergraduate, the more time spent studying did not translate to confidence in knowledge. I agonized over my ability to pass the assessments. My clinical reasoning did not seem to be developing at the same speed as others, despite hours of study. However, knowing I had peers to turn to for questions or reassurance spurred on my learning. Friendships developed at a fast pace as we relied on each other for support, spending most of our waking hours together quizzing each other on bony landmarks on skeletons in practical rooms.

2.2 Call to Adventure

In March 2020, a friend came to my house to study for our upcoming anatomy assessment. Our study sessions had become a regularity in my life. We spent hours quizzing each other and creating studying materials. I felt reassurance from these activities, although fleeting. My anxiety continued to heighten as we progressed to a new phase of the module, moving sequentially through the joints of the body. That night, we began learning about the shoulder joint anatomy, pathology, and testing. I struggled to concentrate on my revision, feeling overwhelmed. My study partner seemed ahead of my understanding. Practical assessments were two weeks away and I did not know how I would cope. The examination involved a face-to-face subjective and objective assessment and intervention on a human model before a panel of three lecturers. Students are randomly assigned a condition of one of the peripheral limbs, unknown to them until entering the exam. Study required wide preparation to cover every peripheral injury presentation that could be selected for the exam.

We spent the night making a list of all the muscles responsible for the possible movements of the shoulder joint. While examining the skeleton, we received an email from our lecturers, informing classes for the foreseeable had been postponed. I remember experiencing a moment of relief. We would have more time to study if exams were delayed. COVID-19 had been in the news for months, and my peers and I had not taken it seriously. We had continued our usual routines, commuting on trains, attending face-to-face classes, eating in the refectory, without restrictions. My study partner and I ended the study session as we became consumed by the student group chat on our phones.

We hypothesized it would be a week before we could return to campus. Our predictions were unfortunately wrong. That night marked the last time I would see another student for six months. I experienced shock as all classes and assessments transitioned online. Although I held hope of a return to campus, the impracticalities of COVID-19 became clearer with each week. I felt frustrated and could not understand how physiotherapy could possibly be effectively studied online.

2.3 Refusal of the Call

The pandemic signaled a call to adventure that I saw no student in my class as wishing to embark on. We had all entered the program fully prepared to be on campus full time. Only then could we have a reflective, embodied physiotherapy experience, through touch (Moffatt and Kerry, 2018). My peers and I previously studied anatomy and applied our learning on each other in practical tutorials. Sensory feedback from manual therapy and handling bodies cemented knowledge gained from pre-reading materials. I learned how to use touch to communicate in a respectful and caring manner while facilitating movement and developing clinical problem-solving practices. With my experience in tutorials, I could not understand how this type of learning could be achieved online. Neither could many of the other students and staff, worrying how they could possibly adapt learning strategies. In group chats, some spoke of taking a year out of the course, with hopes to return to previous ways of doing, being, and thinking post-COVID-19.

Online classes involved the full cohort of students, unlike our previous experience on campus in small groups. I struggled to engage online in a group environment with so many unknown faces. Many other students seemed to experience similar difficulties, reluctant to put on their cameras, microphones, or to write in the chat function. Lecturers tried to engage students by randomly selecting names off the attendance record. However, this led to some students, myself included, feigning technical difficulties and signing out of the class. Anxiety experienced normally when face to face felt heightened online. I stressed for many hours before classes about what questions I might be asked and what the lecturers and cohort would think if I gave the wrong response. The online classroom did not feel a safe place for learning, with high anxiety over the future of our education, and if anything, it felt like it only caused more isolation. COVID-19 instigated a call to adventure into what seemed like a learning dead zone. Even with a strong motivation to engage, I found myself refusing the summons.

2.4 Meeting with the Mentor

COVID-19 changed the way we lived. Instead of huddling over skeletons in practical rooms, we hid away in our homes. The pandemic tore us from our previous identities and routine. Our new reality felt unreal, almost like the script of a movie. I had mornings where, for one blissful moment, I forgot about the pandemic. It never lasted long enough. I tried to stay positive. After all, being at home was not all bad. I had more time to focus on my assessments, without the regular commute to university or my hours working in the clinic. My home environment also afforded room for an office, living area, and a gym space. I knew this to be a blessing many did not have and used the space to create an illusion of my usual routine, separating my living and working environments. The time at home also benefited personal relationships. During the first lockdown, my mother had significant health issues. I valued the extra time at home to be with her as we processed the clinical prognosis of her disease.

I tried to stay connected to friends through messages and video calls. It worked at first, but soon the distance took a toll. No longer having the reassurance of peers, I searched within. I utilized time by creating study materials, learning the language of the human body and memorizing its road map. Authors of journals, textbooks, anatomy applications, physiotherapy social media accounts, and lecturers who provided online resources became my mentors through their creative learning resources. Lecturers stressed their support and availability to students as we dealt with the emotions related to the uncertainty of our new reality. They acknowledged their own difficulties at the time, experiencing new technologies and methods of communication, which required a learning journey for many of the staff. Finding it difficult to engage in class discussions, I struggled in the online environment with around 70 students present. Others, including staff, also seemed to be overwhelmed with the dynamics of the online classroom. We found unison in these emotions, a shared state that connected us all, motivating us to strive forward together.

2.5 Crossing the First Threshold

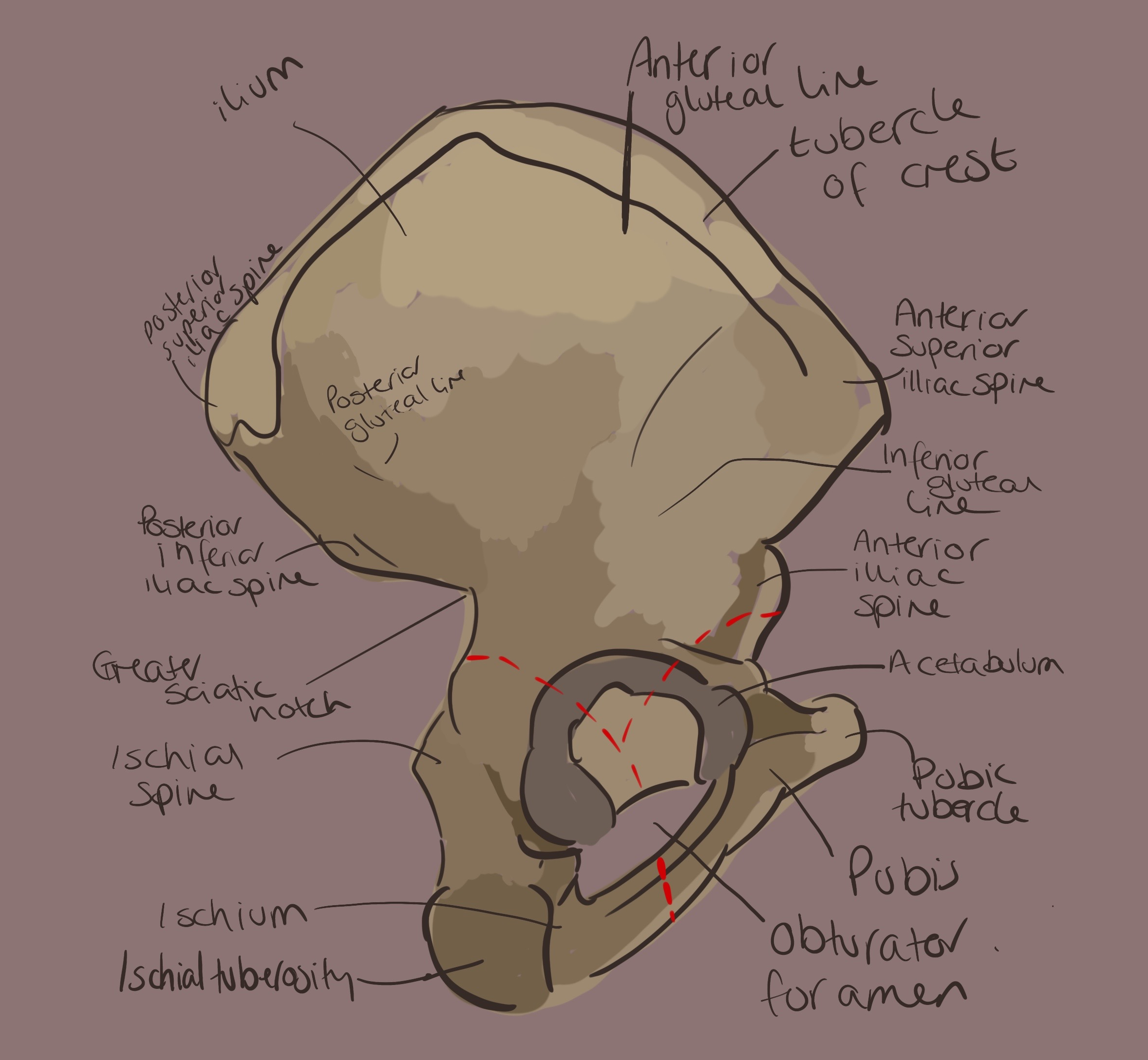

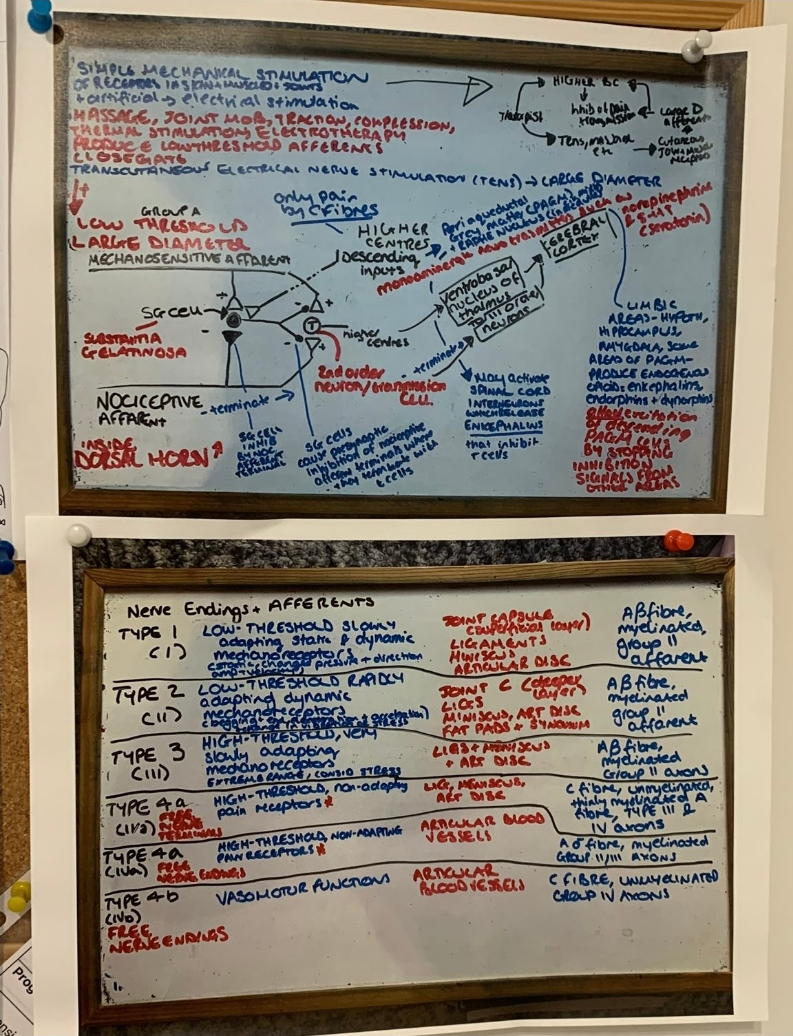

A strong motivation to become a physiotherapist and the support of wide-ranging study materials, from videos of manual handling and therapy skills to mind maps and drawings, pulled me across the first threshold of my story. I began to build confidence in my ability to study online, without the constant comparison of myself to the progress of other students. Studying at home empowered my learning through choice of learning method, time of study, and the flexibility of environment. I filled my home-clinic walls with colorful drawings, mind maps, and notes (see Figures 2 and 3). Although my nerves over assessments remained, the intensity of the anxiety seemed reduced. I no longer felt fatigued all the time, without the constant struggle balancing the commute and work obligations. Having the time to concentrate on my studies felt like a gift.

FIG. 2: Student anatomy drawing

FIG. 3: Student wall study notes

In the end, the hard work paid off and I passed my first assessments, including an online objective structured practical examination (OSPE). The OSPE measured my ability to verbalize manual handling and therapy techniques, using my hands to animate my explanations. My confidence grew, knowing my lecturers thought my abilities to be competent. Verbalizing clinical procedures seemed more challenging than physically enacting, with visible cues available, such as plinth height. If I could speak to someone through each stage in the process of patient assessment and treatment, I believed these cognitive abilities would transfer to physical skills. As a result of online learning, I felt better equipped to begin the next set of modules on the program. My hope for a return to in-person practical tutorials continued. However, I had developed a sense of learner agency, formed through my independent learning over lockdown. Completing the program online, although unconventional for physiotherapy, felt achievable and in some ways, more desirable.

3. ACT 2

3.1 Tests, Allies, Enemies

A tone had been set by lecturers in the first few months of the program between them and students. It pushed us to always come prepared, adhere to class decorum, and value our time with lecturers. This tone emerged likely from the historical culture of the program, with an accelerated nature, and from wider physiotherapy pedagogy. Classes often held an intense atmosphere, for me at least, where I waited to be called out and exposed as an imposter. Prepandemic, students thrived under the pressure, striving to be like their lecturer mentors. This dynamic poorly translated to the online environment and at times meant lecturers could be seen more as enemies than allies. Even when a lecturer attempted to provide a warm and welcoming online atmosphere, the tone set from previous expectations could still be heard in the background.

It is difficult to say where my peers were positioned, as allies or enemies. Many of the students in my year fostered competitiveness. I wonder if this behavior stemmed from the challenges of enrolling in the popular physiotherapy program, with limited spaces of study. It may also be linked to the higher rates of perfectionism found in physiotherapy student populations, with high value placed on attaining the best marks on assessments. I found myself constantly comparing my development to others, feeling the pressure to be a high achiever. However, with a psychology degree rather than a sports, kinesiology, or exercise science background like many of my peers, I felt unable to match their knowledge. Moving online changed my environment from one of constant comparison for self-evaluation to one with greater agency over my anxiety and the ability to focus on my journey, rather than fixate on others.

The online environment did not dispense of the competitive nature within the program. My cohort, as any, had divisions based on peer groups, naturally emerging from relationships developed living in close proximity. Depending on your membership to each group, you had access to certain group resources. For example, on some chats students shared study notes, drawings, and videos. Only as a member of one or more of these groups could you reap the benefit of these resources. Students who did not fit into these groups, such as those not living closely to other students, unfortunately did not have access and experienced a disadvantage. As I did not live with other students, I did not have access to the benefits of peer-curated resources and worried how I might perform as a result compared to the other students.

Although I view a few students as more fitting to the role of enemies than allies, this did not extend to my experience of the full cohort. Some students, all who seemed to have similar experiences that set them apart from the cohort groups, acted as strong allies on my online learning journey. I grew close to one student in particular, meeting online before classes to discuss pre-reading and create our own study materials in live documents. She did not seem to have the competitive nature I often detected in others. Instead, she seemed calm and confident, even when I knew she had concerns around passing. I felt her to be an anchor at times of high uncertainty and stress, keeping my focus where it needed to be, on my development.

Over time, new peer allies emerged, studying through online chats and video calls. My family also acted as allies. Wishing for my success, they offered their time for skills practice (see Figure 4 and Video 1). They supported my embodied development by providing feedback on their bodily experience. Although I benefited from a strong supportive environment, my biggest ally, on reflection, was me. I learned through studying online to be independent, without the dictated schedule experienced on campus. As much as I benefit from peer learning, I achieved many of these benefits working alone, in my own time and approach to learning. My creativity emerged as I experimented to find new ways of study that would help meet my practical learning needs.

FIG. 4: Physiotherapy skills practice at home

Video 1: Student's family offered video time for skills practice. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAEzXrn7PqE

3.2 Approach to the Inmost Cave

During summer modules of 2020, lecturers started to utilize innovative ways to communicate theory and cognitive aspects of practical skills for cardiovascular and respiratory therapeutics and neurorehabilitation. It was understood that the cohort would return to campus when possible to practice our skills in person. Lecturers shared audio files and videos edited using graphics and animation to facilitate an online embodied experience. Understanding students might not have a human body for skills practice, lecturers often used an alternative, such as stuffed toys for demonstrations. My peers and I showcased our understanding by filming ourselves repeating these skills and submitting the recording onto the university platform for lecturer and peer review. Access to the student and lecturer videos provided reassurance of my development in line with other students.

The majority of my cohort seemed to submit videos. However, some seemed reluctant, possibly due to the nature of recording in your home environment, the vulnerability of sharing with a wide and to some extent, unknown audience, and the technology skills required to complete the task. I missed the level of feedback in tutorials provided by lecturers and peers on manual handling, technique, and mannerism. Our cohort were assured, by lectures, of time to receive this feedback during future clinical rotations and on returning to campus. However, reduced availability of clinical rotations and a spell of never-ending lockdowns made the likelihood of achieving the desired practical experience seem unlikely.

My cohort fortunately did return to campus, but not until January 2021. I can clearly remember the image of us as we formed lines outside the university. An electric energy buzzed between us as we waited for lecturers to herd us to practical rooms. One by one we entered the building and found our way to our room and a plinth within. Unlike previous tutorials, each student had been allocated to a group, called a bubble, which they would belong to for the remainder of the preregistration modules. I knew my bubble peers well from previous classes and looked forward to practicing with them. Yet, it felt strange, almost wrong to touch another person. We had spent so much time scared of contact over the pandemic that it no longer felt natural to be close to another even in our plastic aprons, gloves, and masks.

As time moved on, my focus refreshed on our upcoming assessments, marking the last stage of our preregistration modules. Our lecturers used a hybrid approach to learning, with theory covered in online classes and practical components in face-to-face tutorials. Online classes changed size, with classes grouped the same as tutorials. It seemed more students felt comfortable taking to the microphone and chat function to contribute to discussion. A new sense of trust developed among us, never experienced in the online classroom before. It is difficult to know why the hybrid environment positively changed the dynamic. I wonder if the social environment of the tutorials might have something to do with it. Time to socialize in tutorials, which we did not have online during the height of the pandemic, seemed to lead to students embracing the online classes. Access to recordings of online classes also seemed to ease pressure and anxiety, with the need to scribble notes reduced. We had more time to enjoy learning opportunities, knowing the class could be rewatched at a later date.

3.3 Ordeal

Staying within our bubbles helped create a sense of trust between my group. However, it also meant less experience handling other body types and individual social and cultural differences. Not being able to move between plinths reduced learning opportunities that discussions provided. Although grateful to be back with peers, I worried how much my clinical development had been impacted through pandemic-related restrictions on learning as I began my first clinical rotation. Had the pandemic not occurred, I would have finished my first clinical rotation by the summer of 2020 rather than after completing my last preregistration OSPE. I had concerns over how my development compared to pre-pandemic students and how this might impact future development and career prospects.

Due to a shortage of placements, the first two weeks comprised online only eLearning placement followed by a shared rotation with three other students, attending in person each for two-and-half days. The Peer Enhanced eLearning Placement component entailed a variety of community and musculoskeletal case studies (Stears et al., 2022). Students worked together in groups to complete subjective and objective assessments, treatments, and follow-up reviews. My case study involved a work-related knee injury. We created chat rooms to share research and come to a decision about our primary hypothesis of patient diagnosis. With an idea of what might be causing the knee pain, our group divided ourselves into pairs to complete the assessment and treatment. My partner and I took responsibility for the objective assessment. I filmed family members in my home clinic, assessing them like they had a knee injury. We then presented the video in a virtual classroom while a physiotherapist, simulating the clinic environment, fed back the outcome of each test. Hearing the physiotherapist had used many of our measures with this patient helped develop self-confidence in my and peer clinical reasoning.

Clinical rotations are an exciting aspect of the DPT program, with time spent under the supervision and mentorship of physiotherapists in a variety of environments, including acute-care hospitals, secondary care rehabilitation units, outpatient clinics, long-term care, hospice, sports, community, workplaces, schools, and much more. It is through clinical rotations that students develop experience in the key specialities of neurorehabilitation, respiratory and cardiovascular rehabilitation, and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Student experience and evaluations of clinical rotations can be an important factor in career aspirations. Hearing rumors many of our clinical rotations would be online, I wondered how the online case studies would translate to the fast-paced hospital environments, working within multidisciplinary teams, with high caseloads, rather than one patient, and conflicting demands on time. I worried about where all the online training positioned my cohort in comparison to pre-pandemic graduates and suffered strong imposter syndrome at the idea of being called a physiotherapist. As an American citizen, I also did not know how my online studies would translate for degree equivalence and credential evaluation if I decided to move closer to family. The image stored in the back of my mind of a confident, autonomous, post-registration physiotherapist prepared to embark on a new career adventure seemed unrealistic. I experienced the Voglers (2020) ordeal, regressing in my commitment to online learning as I once again questioned my abilities to perform in the embodied ways expected of physiotherapists (Langaas and Middlethon, 2020; Latour, 2004; Skulmowski and Rey, 2018).

3.4 Reward

The second part of my first clinical rotation involved a high level of peer learning in an inpatient pediatric hospital. Similar to the eLearning placement, I attended online for the majority of the two weeks. I did not feel excited by the idea of continued online learning for my first clinical rotation. Each day one student arrived on site at the hospital and connected with the other three students, attending from home, through a Microsoft Teams call. Knowing the other students well, all like me, on the doctorate route, offered some comfort. However, I wanted to be in the hospital every day with my clinical educator, fully embodied in the experience. To my surprise, using this placement model had many benefits. It allowed the students at home to support the onsite student by researching conditions as required and instantaneously. My clinical reasoning benefited from the new perspective developed through peer discussions. We worked as a team to assess and treat patients, with no individual making a decision alone. Following patients' recovery after discharge, we used the embodied communication skills developed through studying online to keep in touch with patients and track progress. We verbalized easy-to-follow instructions of movement learned through the pandemic, providing feedback as we observed the pediatric patient through a virtual platform.

With this experience, I felt more certain about my physiotherapy skills due to positive outcomes from interacting with peers and patients. Feedback from clinical educators added validation to my abilities, with educators rating my performance as similar to new graduates. I finished my first clinical rotation feeling optimistic about my physiotherapy reasoning and skills. The online peer collaboration involved in both parts of the rotation allowed my eased transition to patient-facing environments, allowing confidence to build with the support of other students, ready to step in to help if needed. Unlike the initial online classes during lockdown, the eLearning placement allowed for time to socialize, allowing us to feel comfortable virtually around each other to exchange and share information necessary for knowledge construction and development (Salmon, 2013). This experience marked the end of Vogler's (2020) Act Two, discovering and laying claim to the rewards of my online learning experience.

4. ACT 3

4.1 The Road Back

“The road back,” for Vogler (2020), presents the hero with a choice, to return home, to the ordinary, or stay in the new online world. Reflecting back to the beginning of my degree, I would never have imagined nearly a year of online learning. My vision of a physiotherapist linked intrinsically to a romanticized relationship between expertise and embodied, hands-on clinician's education. Physiotherapy's gold standard of education found in the ordinary world can be described as lecturer-led face-to-face skills practice on campus. This image of physiotherapy is depicted in photographs found inside student textbooks and online resources (Palastanga and Soames, 2019).

The photographs highlight the importance of touch in physiotherapy skill development. Considering any alternative means of educating students might be seen by some as inferior. I admit once feeling very much of this mindset. However, as we head on the road back from our unwanted adventure, the taste in my mouth no longer is bitter. I can hold my head high knowing my education prepared me well for my first clinical rotations and practice educators to think me competent.

4.2 Resurrection

Currently, I am near the end of my fifth clinical rotation in an outpatient orthopedic and sports physical therapy clinic in Texas, marking the resurrection of my journey. This stage provides a final challenge for the hero. My rotation has certainly fulfilled that promise. Working in another health care system, consisting of DPT graduates only, has proved an adjustment. I found myself, similarly to when I attended face-to-face practical classes, immediately comparing my knowledge and skills to other DPT students. Skill differences were apparent between us, and I felt ashamed and fraudulent in my role. I did not know if I should blame the online practical classes or wider physiotherapy educational differences between Scotland and the United States. Maybe I used both as an excuse. But mostly, I blamed myself for my lack of clinical proactivity since my preregistration exams. I had comforted myself in the knowledge I had passed my practical modules and focused my attention on academic pursuits. Now the cracks in my foundation were showing.

The weeks went by and I realized the steep learning curve I experienced might not be related to learning practical skills online but a normal occurrence for my current stage in my learning journey. All my previous rotations had been in inpatient hospital environments where I had not used the same neuromusculoskeletal assessment and treatments found with outpatients. It would be unusual for a new student to be as experienced as the others in the clinic, who had several weeks of experience already. My practical educator reassured me of this and eased my transition into the outpatient environment. It seemed she put great efforts into making me feel safe and comfortable in the new environment.

Climbing the steep learning curve, I used my self-directed study skills gained during the online classes. I revisited the online resources the university had supplied, going through PowerPoint presentations and videos to refresh my unused skills. My practical educator acted as an ally by offering her time, patience, and available resources to bridge any learning gaps in my learning. With positive reinforcement and a welcoming clinical environment conducive to learning, my anxiety eased, and I began to feel as though the rotation might be my best clinical experience to date.

I cannot say I feel fully resurrected at this point in my story. When I compare myself to the physiotherapist envisioned at the beginning of my degree, I find myself lacking. However, I feel more at peace with the pandemic-related changes to my education and appreciate the anxiety and uncertainty I often associate with online learning to be misdirected. It is not because of my online education that I feel like an imposter. Rather, I have not met my personal and professional development goals, which are admittedly high, and achieving then will require years of more clinical experience. As I leave this stage, I do not feel the same optimism experienced after my first rotations as I process my metaphorical brush with death. I will undoubtedly still battle demons as my learning journey continues, but I am happy to say they will no longer be emerging from dissatisfaction over pandemic-related online changes to my degree structure.

4.3 Return with the Elixir

The introduction of online learning had the potential to enhance the learning journey for many students, with its flexibility, greater resources, less financial strain associated with travel, improved work–life balance and learner agency. Moving to online education for our program was an action born from a desire for program survival rather than progressive teaching styles. I do not think any person, lecturer nor student, wished this adventure upon us. However, we rallied together and entered the online world with fear in many hearts. Although initially discouraged and challenged, I came to see the value of online learning for developing self-directed study, taking control of my learning with less reliance on peers and lecturers as a guide and support system. One of the greatest benefits of online practical education involved learning how to assess and treat a patient through verbal communication and hands-off demonstrations of movement. Lecturers as well as students experienced a mindset shift as they adapted to the distance created by the pandemic. Being able to articulate my knowledge without relying on my body language or hands-on skills increased my confidence and aided future placements when using telehealth services. I contacted patients through video and phone calls, verbally communicating tacit knowledge. The use of these skills enhanced access to the patient with them able to attend a service from home without reducing the quality of healthcare.

5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Using the Volgler (2007) hero's journey has proved a useful tool in facilitating my reflection of online learning during the pandemic. I have grown to see the value of online learning and the potential evolution. However, the embodied nature of online only learning seems to be lacking. Many of my peers and I found difficulty adapting to the online environment, feeling overwhelmed by the large online classrooms and expectations placed on us by lecturers. The inability to see or hear other students, I believe, disconnects us and reduces the shared learning experience. However, as digital pedagogy grows, I am certain this obstacle will be overcome and new exciting ways of doing, being, and thinking in the online environment will emerge.

5.1 Recommendation 1

Use a hybrid approach to embodied learning until an online environment fostering the skills, knowledge, and behaviors required for physiotherapy has been developed. The hybrid approach might form the elixir of the future learner's journey as it allows the best of both worlds. Reframing embodied learning through an online lens may promote greater learner agency and responsibility. The skills learned in online learning will aid preparation for the changing demands of the current workforce, with virtual healthcare environments, such as telehealth.

5.2 Recommendation 2

Adopting digital pedagogy in curriculum design can support staff and students to make informed choices on how to use technology for learning and teaching. Digital pedagogy can be used to dispel a variety of misconceptions on the use of technology and online learning for practical skills. There needs to be an ontological shift away from the current gold standard of physiotherapy in-person learning to hybrid/online learning for the evolution of teaching practices.

5.3 Recommendation 3

Use co-creation practices to promote student responsibility over the learning environment and the creation of learning resources, including problem solving and using innovative methodology. Ensure skills developed online are transferable to wider employability, with embodied learning taught explicitly. Students should also be mindful of digital identity and well-being (Jisc, 2018).

5.4 Recommendation 4

Online educators should consider the best methods to facilitate a safe learning environment for group work. Promoting a sense of belonging within the online space can facilitate collaborative learning between students and improve the learner experience online. For successful collaboration, students need to develop rapport through trust and mutual respect. Educators need to consider the context, appropriate technology, and guidance for online interaction. This provides a platform for meaningful interaction, thus promoting a sense of belonging.

REFERENCES

Gourlay, S. (2005). Tacit knowledge: unpacking the motor skills metaphor, Sixth European Conf. on Organisational Knowledge, Learning, and Capabilities, Waltham, MA, USA, March 17–19, 2005.

Jisc, Building digital capability: The six elements defined [Framework]. Jisc, Bristol, UK, September 2018; accessed August 21, 2022 from: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/building-digital-capability

Kontos, P. C. & Naglie, G. (2009). Tacit knowledge of caring and embodied selfhood. Sociology of Health & Wellness, 31(5), 688–704.

Land, R. (2019). The labyrinth within: Threshold concepts, archetype and myth. Threshold concepts on the edge, Brill Sense, Leiden, pp. 3–18.

Laird, J. D. & Lacasse, K. (2014). Bodily influences on emotional feelings: Accumulating evidence and extensions of William James's theory of emotion. Emotion Review, 6(1), 27–34.

Langaas, A. G. & Middelthon, A. L. (2020). Bodily ways of knowing: How students learn about and through bodies during physiotherapy education. Mobilizing Knowledge in Physiotherapy, Routledge, London, pp. 29–40.

Latour, B. (2004). How to talk about the body? The normative dimension of science studies. Body & Society, 10(2-3), 205–229.

Moffatt, F. & Kerry, R. (2018). The desire for “hands-on” therapy—A critical analysis of the phenomenon of touch. Manipulating practices: A critical physiotherapy reader, Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP, Oslo, pp. 174–193.

Nicholls, D. A. & Gibson, B. E. (2010). The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26(8), 497–509.

Polanyi, M. (1962). Tacit knowing: Its bearing on some problems of philosophy. Reviews of Modern Physics, 34(4), 601–616.

Salmon, G., (2013). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. Routledge, New York, 2013; accessed August 21, 2022. DOI 10.4324/9780203074640

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Palastanga, N. & Soames, R. (2019). Anatomy and human movement, structure and function, 7th Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, Edinburgh.

Stears, A., Thomas, J., Lane, J., Salisbury, L., Rhodes, J., Ackerman, L., & Baer, G. (2022). The evaluation of a Peer Enhanced eLearning Placement (PEEP) in MSc Physiotherapy (preregistration) education. Physiotherapy, 114, e18.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2002). Introduction to the special topic: Epistemology and movement. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 29(2), 103–105.

Skulmowski, A. & Rey, G. D. (2018). Embodied learning: introducing a taxonomy based on bodily engagement and task integration. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 3(6).

Vogler, C. (2020). The writer's journey: Mythic structures for writers. 25th Anniversary, 4th Ed. Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City, CA.

WCPT. What is Physiotherapy? World Confederation for Physical Therapy (aka World Physiotherapy), London, 2022; accessed at https://world.physio/resources/what-is-physiotherapy

Comments

Show All Comments