TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING IN ONLINE COLLEGE COURSES: PROCESS AND EVIDENCE

Abstract

This overview of the University of Central Oklahoma’s Student Transformative Learning Record initiative describes how the institution operationalizes Transformative Learning, primarily in its undergraduate program, and specifically within online classes. Examples of two faculty assignments in online classes that were associated with Transformative Learning outcomes are described, along with student responses that indicate different levels of advancement toward transformation. Also reported are faculty observations about the institution’s process, specifically and in general, how Transformative Learning translates into the virtual environment.

KEY WORDS: transformative learning, rubrics, authentic assessment, beyond-disciplinary learning

1. INTRODUCTION

Transformative Learning (TL) began with the theoretical reports by Jack Mezirow in the mid-1970s [see Hoggan et al. (2017), Kitchenham (2015), Swartz and Sprow (2010)]. His introduction of TL theory was quickly followed by Christie et al. (2015), Cranton (1998), Dirkx (2001), Nerstrom (2014), and Taylor (2017). Critical reflection is a key component of TL (Taylor, 2017) because learners must reflect on the circumstances encountered when a disorienting dilemma, the triggering mechanism at the start of a potentially transformative experience (Mezirow, 1991), challenges learners’ conceptions of their place in the world and/or the assumptions upon which they have built their interpretations of how the world works (Mezirow, 2000, 2006). This process of TL is summarized by Cranton (1998) as that which occurs when we are “led to reflect on and question something we previously took for granted and thereby change our views or perspectives” (p. 192).

TL has had a major impact on the field of adult education, as its genesis began with adult learners who faced disorienting dilemmas about their own place in family, society, and what that place required of them educationally (Mezirow, 2000). As the college student population in general has changed in recent decades, with more older adults returning for their first or subsequent degrees and certificates, over half of college-goers today are independent students with a median age of 29 (Reichlin et al., 2018), which means that TL is highly applicable to them and their educations. But transformative moments know no age boundaries, and with college seen as a place where students are supposed to develop beyond-disciplinary skills such as how to work on teams with people different from them, how to lead effectively when the situation demands, and how to be a life-long learner (Bridgstock, 2009; Hart Research Assoc., 2013, 2015, 2018), coming to some personal transformative moments as an undergraduate at some age between 18 and 22 is probably a necessity.

Boyer et al. (2006), Henderson (2010), and Jackson and Chakraborty (2014) have made compelling cases that TL is possible, appropriate, and in some ways even ideally suited within the online environment. This article will proceed from that perspective and describe the process and tools the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) employs that have faculty mindfully and intentionally planning assignments and activities designed to prompt students’ transformative realizations—and track and assess their development in doing so—in connection with one or more of UCO’s Central Six Tenets: Discipline Knowledge; Global and Cultural Competencies; Health and Wellness; Leadership; Research, Creativity, and Scholarly Activity; and Service Learning and Civic Engagement.

2. TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING AT UCO: WHAT PRIMED THE PUMP?

UCO has about 14,500 undergrad students, and about 1500 grad students. The institution is relatively new to online programs, although there currently already are some fully online programs. About 21% of credit hour production comes from online and blended/hybrid classes. The Student Transformative Learning Record (STLR) is primarily a component of the undergraduate program, but some graduate faculty have STLR components in their courses.

In the late 1990s, UCO leadership began to see student success-centered initiatives popping up around campus, something that continued into the new century. The strong sense that “it’s all about the students” has been part of the culture of UCO since its inception as a teaching institution. Sometimes these initiatives were department- or college-based, sometimes institutional in scope, sometimes the brainchild of an individual or a small group, but they all were demonstrably focused on helping students succeed, develop as humans, and gain new perspectives. Examples include: the American Democracy Project, the Peer Health Mentors program, and formalizing an undergraduate research focus.

All these initiatives were laudable and launched in service to student success. Leadership wondered, though, if some kind of organizing umbrella existed under which these disparate programs could logically nest, and which would group activities into like areas, thereby helping the campus community and external constituencies understand the uniqueness of the UCO education. The President’s Cabinet’s consideration of Transformative Learning for this purpose was prompted by a review of ideas set forth in Learning Reconsidered and Learning Reconsidered 2 (Keeling et al. 2004, 2006). That review and other considerations cemented the concept of TL as an appropriate focus for the kind of education UCO wanted to provide for students. Formalizing the alignment between TL and UCO’s focus on helping students learn and develop important life skills occurred when UCO placed TL in the mission statement in the 2008-2009 academic year:

The University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) exists to help students learn by providing transformative education experiences to students so that they may become productive, creative, ethical and engaged citizens and leaders serving our global community. UCO contributes to the intellectual, cultural, economic and social advancement of the communities and individuals it serves. (UCO, n.d.)

Concurrent with adopting TL as a university focus, UCO placed its Central Six Tenets, (Discipline Knowledge; Global and Cultural Competencies; Health and Wellness; Leadership; Research, Creativity, and Scholarly Activity; and Service Learning and Civic Engagement), as the means of grouping student success activity, whether in the classroom or beyond. The ‘C6’ and TL were promoted tirelessly to faculty and all constituencies by the Provost/Vice President for Academic Affairs, and UCO began a number of actions to help faculty understand TL and adopt its practice. One initiative was the Transformative Learning Steering Committee, a group with wide representation from across campus, convened to help UCO Figure out how to ‘do’ TL. One activity the Committee undertook was to implement an annual day-long, institution-wide conversation about TL at UCO, initially named the “Share Fair 2008: Partnerships in Transformative Learning” (University of Central Oklahoma, 2008) but which quickly became the annual, now a national/international convening of higher education practitioners in ‘doing’ TL.

In spite of these and other initiatives between 2008 and 2012, however, TL had yet attained widespread implementation in classes. Consequently, in early 2012, UCO began working on a a formal plan to operationalize TL across both the curriculum and the co-curriculum (i.e., learning and development activities that happen outside for-credit coursework). Thus was born the (STLR).

3. STLR: UCO’S VERSION OF TL

Simply put, the Student Transformative Learning is process, tools, infrastructure, training, and technology that allow faculty and staff to intentionally design, track, and assess activities in both the curriculum and the co-curriculum to help students achieve transformative realizations within an authentically assessed, evidence- and badge-based environment. UCO’s operational definition of TL is that it 1) develops students’ beyond-disciplinary skills, and 2) expands students’ perspectives of their relationship to self, others, community, and environment.

The Tenets are the broad categories within which beyond-disciplinary skill development and/or perspective expansion can take place. Faculty adapt existing assignments, associating them to one or more Tenets by having students create a STLR learning artifact, which is some form of reflection about the associated tenet(s)’ connection to the assignment.

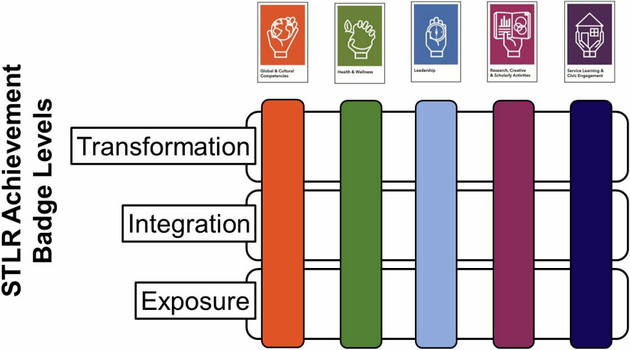

An example from training materials for faculty incorporating STLR in their courses is the Global and Cultural Competencies Tenet associated with a homework assignment on the Central Limit Theorem in a statistics class. If the instructor previously had students use a dataset that came with the textbook, she could now have students go to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) or similar website to find datasets about how many kilometers villages in certain parts of the world are from the nearest source of potable water; meaning, how far do the women in the village (typically the case) have to walk to get water and haul it back to the village? This new dataset works just as well as the one the instructor has used for years, but it allows her to associate the Global and Cultural Competencies Tenet to the assignment by requiring students to answer a well-constructed reflective prompt about the notion of the nearest source of drinking water being X kilometers away, the hours-long round-trip hauling water, and the impact it has on humanity in the region. The assignment is graded as it always has been, but the instructor also assigns one of three badge achievement levels to the reflections the students provide. Figure 1 shows the badge levels across the beyond-disciplinary Tenets. (Discipline Knowledge as a Tenet is assessed via grades because the academic transcript is the existing mechanism to convey disciplinary knowledge achievement.)

FIG. 1: Achievement badge levels across beyond-disciplinary Tenets

Important to note is that the rubrics used to assess achievement toward ‘Transformation,’ the top level, are not constructed such that a necessarily linear progression occurs up to the Transformation level. It is not the case, for example, that after X Exposure-level assessments in Leadership assignments that the X+1 instance automatically earns the student the Integration level assessment. UCO’s Tenet rubrics are adapted from the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education), and fidelity to the rubrics is emphasized in faculty training about TL, STLR, rubrics, authentic assessment, creating good reflective prompts, and other topics covered during STLR training for faculty and staff. This evidence-based process that stays true to the rubrics means a student might receive a Transformation-level assessment, for instance, even before receiving an Exposure- or Integration-level assessment, as could be the case with a student from a military family who has lived all over the world when she responds to her first Global and Cultural Competencies prompt in some assignment during her first semester at UCO.

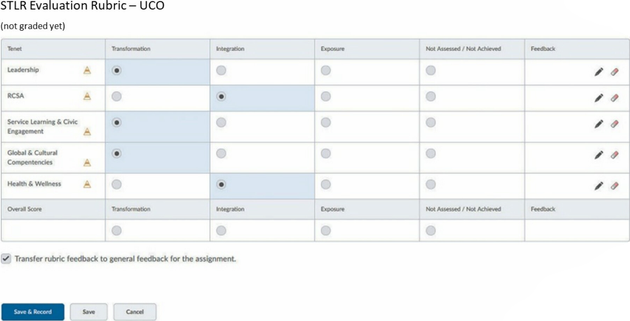

Minimizing work for faculty and staff has been a hallmark of STLR development; hence the training to adapt existing assignments to Tenets, thereby avoiding the need for faculty to create something new and an additional ‘separate thing’ for their classes in order to ‘do STLR.’ Within the course shell, the faculty member cursors her mouse over the cell in the STLR rubrics matrix that corresponds to the Tenet and rating she wants to assign, then clicks to record the assessment (Figure 2.)

FIG. 2: STLR assessment process within the course shell

The STLR learning artifact, the rating the instructor assigns, and the STLR Tenet rubric used to assess the artifact are all associated into students’ dropboxes in the course shell. From there, students push that material to their STLR eportfolios, ultimately using that raw material to create finished eportfolios—which can be created and saved in multiple versions—for use in job or graduate school applications along with their STLR Comprehensive Learner Records (CLRs), which document their beyond-disciplinary development. Students receive instruction in how to create and use both the CLR and the eportfolio via some combination of engagement with the eportfolio as part of the freshman seminar class and/or capstone course work and/or engagement with UCO’s Career Development Center (though students can also receive help with this if they are in classes where individual faculty have prescribed eportfolio work as part of the classwork).

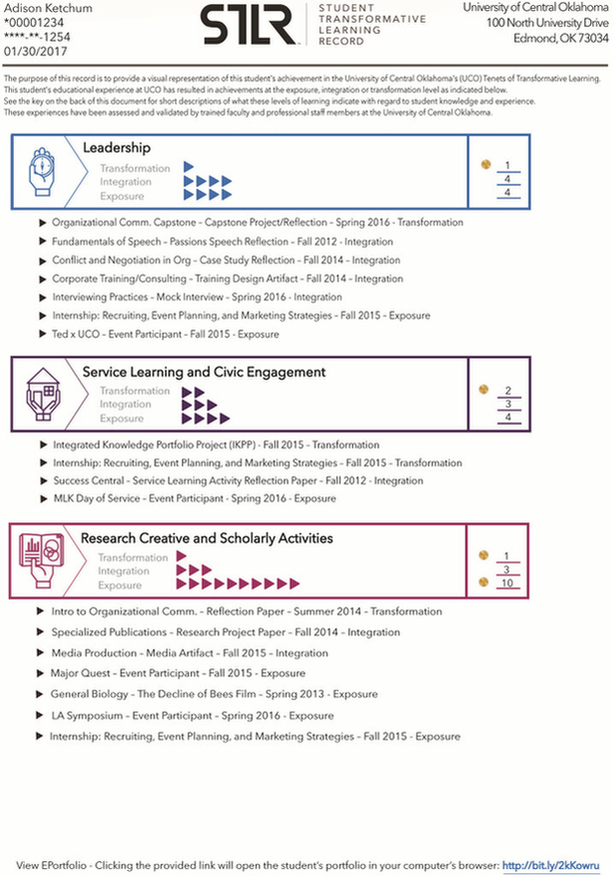

Figure 3 illustrates the CLR, which carries the Registrar’s seal:

FIG. 3: Sample of STLR CLR

UCO values the CLR as an asset-based record, not a deficit-based record; meaning, everything on the CLR is 1) vetted by UCO via STLR rubrics and assessment, and 2) customizable by students. This means students can choose not to show an activity in a Tenet if the CLR they are building for a particular use should give more emphasis to other activities and/or other Tenets. Students can also customize the order in which the Tenets are shown on the CLR and the order of the individual engagements listed for each Tenet. This is similar to customizing a cover letter to highlight at quick glance what would catch a hiring manager’s eye. It was also important that the CLR be a formative tool to help students; to that end, UCO is now beginning to require CLRs as part of the application process for awards, student worker positions, applications for student group officer positions, and so on—this gives students the chance to practice using the CLR (and the STLR eportfolio, for that matter) to help them make compelling presentations of self during interviews before they do so in the real world on job or graduate school interviews.

4. ONLINE STLR AND ONLINE STLR ASSESSMENT

With the place STLR ‘happens’ regarding tracking and assessment being the Learning Management System course shell (in UCO’s case, D2L/BrightSpace), online instructors ‘do STLR’ in exactly the same way as do face-to-face (F2F) instructors. The key to successful ‘STLRizing’ (yes, UCO has made the acronym, “STLR,” a noun, an adjective, and a verb) is associating an impactful beyond-disciplinary learning opportunity to an assignment, creating an effective reflective activity and prompt, and assessing accurately using the Tenet rubrics.

STLR at UCO is assessed in multiple ways, including for inter-rater reliability among faculty, as well as for the percentage of assessments at each of the badge levels. With STLR now into its fourth year of broad implementation, assessments at the top badge level of Transformation are holding at between 9%–12% of all assessments during a semester. This percentage includes online STLRized classes, which are counted among the totals tracked every term.

What does an online STLR assignment look like? The following example is from the “Problems of Today’s Consumer” class, a course that presents the economic aspects of purchasing for the consumer, including consumer credit, protective agencies, principles of consumer choice, consumer services, and the family as a center for consumer education.

For her “Problems of Today’s Consumer” class, the instructor saw a clear connection to the Health and Wellness Tenet because of the physical/emotional toll taken by stress fomented by financial insecurity. She has students write papers early in the class to self-identify about their level of knowledge concerning finances, budgeting, and so on. Later in the class, one of the writing assignments has students responding to the prompt, “Would you share this knowledge [of budgeting] with others?” One student responded to the prompt by saying the knowledge had changed her life because she had never done a budget before, but knowing how to do it now has empowered her, and that she immediately began teaching her kids how to budget.

Likewise, in the writing assignment that had students reflect about aspects of nutrition (yes, there is a connection between nutrition and budgeting), one student wrote that the information led him to change his diet and to start getting some exercise. His self-disclosure in this writing assignment further revealed that the way he decided to get more exercise—walking—had also resulted in his spending more time with his wife because they went walking together, and he shared that this had helped the two of them rekindle intimacy that had fallen prey to the busy-ness of life.

These assignments in this online class were assessed using the STLR rubrics for Health and Wellness. The instructor helps students understand the difference between the three badge levels—Exposure, Integration, Transformation (from low to high)—by letting them know that a key aspect of determining whether a student goes beyond Exposure concerns the difference between what one “could have done” in terms of a rational, conscious awareness versus “what you experience,” helping make the point that transformation is an experience, not just a “knowing.” This instructor makes clear in this online class (and she does similarly in F2F classes) that receiving Exposure-level assessments on reflective assignments is perfectly fine, that it has absolutely no bearing on one’s grade.

Before moving to a second example of assessing student reflective work related to Tenets, it is important to emphasize the separation of assessment for development of beyond-disciplinary skill and perspective transformation (STLR) and the grade received for the assignment and ultimately in the class. When faculty associate one or more Tenets to an assignment, they continue to use whatever grading scheme they have always used to grade the assignment. For the reflective component required of students that connects to the Tenet(s) with which the assignment is associated, however, the STLR rubrics are used, and the badge level achieved has no connection to the grade on the assignment.

This was an initial concern for faculty when STLR was introduced. They worried that high-achieving students would badger them about not receiving Transformation-level ratings regularly (faculty were prescient in realizing that Transformation-level ratings would not often be assigned) or that students would try to ‘game the system’ in their reflective narratives to achieve a Transformation-level rating based on a compelling but personally untrue and inauthentic telling of their internalizations upon reflection. As illustrated by the instructor above in her online class about personal finance, faculty have found that reassuring students that the STLR assignment has no grade impact helps, as does explaining that a student’s journey toward transformative realizations can take unexpected turns along a path that stretches across the entire undergraduate degree, with those impactful a-ha moments lying in wait to be triggered at any moment; in other words, receiving Exposure or Integration is never a failure, it’s just a step, and that is a good thing.

Also of note is that STLR documents what is going on in student beyond-disciplinary development. In the above example of the student changing his actions to be more healthy—clearly a transformative moment in his life, especially given the side benefits that accrued regarding his relationship with his spouse and his recognition of that fact—such a student may very well have shared that with an instructor who, at another institution with instructors giving similar assignments but without STLR, would have listened with satisfaction and pride that their engagement with the student resulted in an important life change. However, the evidence this happened, and the assessment that occurred based on highly regarded rubrics, would simply not exist without something like STLR.

It is not an inconsiderable aspect of STLR that faculty are trained in how to intentionally create assignments, activities, and environments designed to prompt a-ha realizations and to track and assess this. The result, naturally, is more transformative realizations among students than if this had been left to chance.

STLR has been embraced by students, and as UCO has continued its implementation and expanded the number of STLR opportunities available in classes, at Student Affairs events (which are auto-assessed at the Exposure level via student ID card swipe-in to the event because mere attendance guarantees nothing except exposure), within student groups and organizations, or by working with faculty or staff mentors on outside-of-class research, students are now becoming conditioned to look for STLR opportunities. One external-motivation reason is that one or more Transformation-level assessments received means the student earns a STLR honor cord in that Tenet (and Tenet color) which is presented in a separate STLR cording ceremony the Friday morning before the semester’s graduation ceremonies begin in the afternoon. (Even given the growing enthusiasm for STLR among students, though, UCO’s number of Transformation badges awarded as a percentage of all STLR assessments has held steady in the range mentioned above.) Students wear STLR cords at the regular graduation ceremonies, and the graduation program notes Transformation badge achievement in the respective Tenet(s) by students’ names.

A second example of an online class with STLR assignments and assessments is from “Introduction to Organizational Communication,” a sophomore-level class. The instructor teaching this class has taught it in both F2F and in online formats, associating the STLR Tenets of Research, Creative, and Scholarly Activity (RCSA) along with Global and Cultural Competencies (GCC) to the course. The reflective activity for these two Tenets is part of the ‘knowledge snapshot page’ assignment near the end of the course connected to the presentation students do about their assessment of the organizational culture of a company, non-profit, or other organization of their choosing. In the online class, the format for this presentation is a narrated slide deck posted to the web that the class can access. (In the F2F version of the class, the instructor has students make the presentation in person to the class using a slide deck.)

This instructor reports that each time she has taught the class, whether F2F or online, she usually has 2–3 students from among a class size of 20 or more who achieve the Integration level in the GCC assessment. All students generally assess at the Exposure level in RCSA.

What does each of the categories mean with this assignment? Exposure-level narratives are generally descriptions of what the culture is at the organization selected for the report. What pushes students from Exposure into Integration on the GCC aspect of the assignment, is reflection by the student that indicates the student is already doing within an organizational culture what she now understands to be beneficial to self and the organization or that she clearly knows what that is and how to accomplish it, with plans for doing so, when she joins an organizational culture as an employee. In contrast, a Transformation-level badge achievement as demonstrated in a narration or presentation would need to include evidence that the student has described “the impact the assignment had on his or her understanding of organizations and the ways the student can apply learnings from the cultural analysis to other areas of life”—this explanation is highlighted on the STLR rubric for Cultural Competencies shared with students.

One example of a student’s narrative in this class that fit the instructor’s rubric for reaching the Integration level for Cultural Competencies is the segment below (per IRB guidelines for UCO STLR research, students and faculty remain anonymous):

This year I am the promotions director for the Student Programming Board, so I will have more access to organizational documents and expectations to Figure out what our culture is like both overall and within the executive board. I think it will be interesting to use this kind of analysis to change how I approach my role within the organization and look at how we are run. Learning more about the importance of communication, being and having a mentor, and creating a family atmosphere will help me shape our plans for the year. Applying these concepts to how the board handles and treats general members will make a big impact on member retention and overall satisfaction with the organization. Hopefully these insights will spill over into all of the events that we do so that students attending our events will see that we are a clan culture that wants everyone to feel included, welcome, and like they can communicate anything with us. (UCO undergraduate student, 2017)

In contrast, a typical Exposure-level assessment is characterized by the excerpt of student writing below, which is a description of what has been observed:

This assignment helped me become more aware of what an organization entails and there are TONS of different people to do different jobs for a reason. It takes a lot to have a successful origination and you have to make sure everyone is included in doing so. (UCO undergraduate student, 2017)

In both instructors’ cases, adapting the STLR process to the online environment was judged to be easy, with the online modality of the course being a non-factor regarding ‘doing STLR’ from an operational standpoint. As with all STLRized assignments, the key consideration is in associating one or more Tenets to an existing assignment in a way that makes sense and affords the opportunity to create a meaningful, well-constructed prompt for students to reflect on their own development relative to beyond-disciplinary skill and/or what might have changed or grown in their interpretations of themselves and the world.

In other words, the online environment for these instructors meant adapting the mechanisms of student presentations but not the approach to ‘doing STLR’ in order to assess students’ advancement toward transformative realizations. For example, the Organizational Communication instructor required both online and F2F students to create slide decks with visual evidence shown to support their contention that the organization they studied had a certain kind of culture, but online students’ decks had to include in slide notes what the students would have said in person for each slide had the presentation been given live to their peers, while the F2F students used their slide decks as part of their presentation, with their spoken narrative taken into account as part of the overall presentation grade. This is not an accommodation requiring a fundamental adjustment to the idea of student reflection as prompts to growth.

However, one of the instructors said she felt the online environment was particularly well suited for students’ self-reflections. As one finds with journaling, where self-revelatory insights coalesce over time until they can be articulated clearly with language, an online class in which students produce weekly journal writing allows students to see their own change over time (Kessler and Lund, 2004) but in an environment that can be deemed a little safer for self-disclosure because of the more anonymous, avatar-like nature by which students come to know one another. E-journaling is also convenient and can be effective in online classes (Muncy, 2014).

5. STLR IMPACT

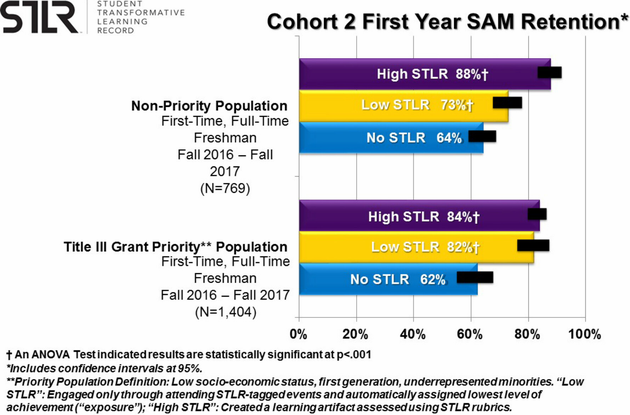

While UCO has not yet disaggregated online STLRized courses from F2F STLRized courses due to relatively small Ns for online classes, STLRized class results regardless of delivery modality (F2F, hybrid, online) in aggregate show p < .005 or better significance levels for association to improved retention and academic performance as indicated by GPA. Figure 4 shows retention results for UCO priority and non-priority populations among the 2016 entering first-time/full-time cohort, the second in which STLR was in broad roll-out for incoming students, and tracked through start of their sophomore year as determined using the Student Achievement Measure (SAM) calculation, which does not penalize the original institution for non-returning students if they have enrolled in another institution the following year (unlike IPEDS calculations):

FIG. 4: Cohort 2 First Year SAM Retention

Results for Cohort 1, which started in autumn 2015, showed “High STLR” and “Low STLR” in the mid-70s percentage-wise and a double-digit lifts compared to non-STLR students. Understandably, UCO was delighted with those first cohort results, too, and even more delighted that Cohort 2 results associating to STLR were even better. Regarding “Low STLR” and “High STLR” breakouts; please understand that “Low STLR” means STLR assessments at the Exposure level as gathered via student ID card swipe-in to a STLR-tagged event, while “High STLR” indicates STLR engagements that were assessed at one of the three badge levels by faculty or staff because students produced required reflective artifacts as part of the activity or assignment.

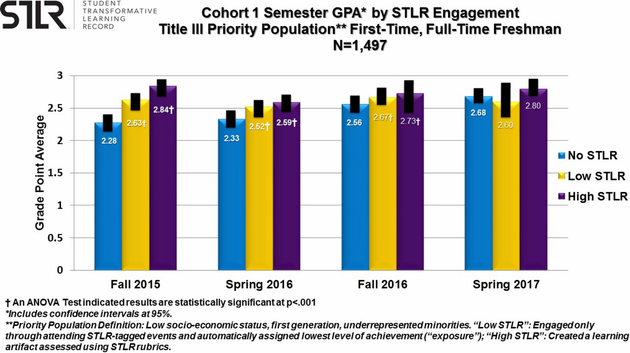

STLR’s association to academic performance is illustrated in Figure 5, which refers to the fall 2015 cohort, this time showing GPA as associated with STLR across students’ freshman and sophomore years:

FIG. 5: Cohort 1 GPA for freshman and sophomore years

As gratifying as these results are, they are complementary to STLR’s main purpose, which is to help students develop beyond-disciplinary skills and to expand their perspective of their relationships to self, others, community, and environment. STLR’s efficacy in that regard will come with employer and graduate school feedback about the performance of UCO’s STLRized graduates. The first graduating class to include students who attended all four years of undergraduate work when STLR was in broad roll-out for their cohort will walk across the commencement stage in May 2019. UCO has from the beginning of STLR planned for a 6-months-out post-graduation survey of employers to find if STLR-prepared new hires are, in general, performing differently in their new jobs.

There are already, though, tantalizing clues. UCO has worked with its STLR Employer Advisory Board for over three years, with that group providing invaluable feedback and suggestions regarding the STLR CLR (Figure 3), the STLR eportfolio, messaging to employers in general, and a host of other topics. Board members have also served to do mock interviews with students who at the time had a substantial number of STLR engagements and to review their CLRs and their eportfolios. As one of the Board members who conducted a STLR student interview said:

My expectations initially, based on experiences with near-college-graduates or recent college graduates, is [of ] their inability to articulate to me [how their prior work experiences and/or internships translate] into real tangible work product or work-related things. So my expectations were that that would occur again, especially with someone who hadn’t graduated.

I found quite the contrary in my interview, and even the review of the eportfolio with this UCO student. In fact, she took experiences from jobs and industry and hourly kind of part-time college jobs that you would expect a college student to have, and transferred skills and knowledge from that into hard-and-fast employer questions that I ask every candidate, and did a better job than folks I’ve had with years of experience and years of situations to draw upon.

That was probably the most profound thing for me. The other was that she dispelled this myth… that millennials and recent college graduates aren’t able to provide value to our workplaces because they don’t have those experiences. (Lance Haffner, STLR Employer Advisory Board member and currently VP Human Resources at Heartland Payment Systems; from a video interview conducted March 2016).

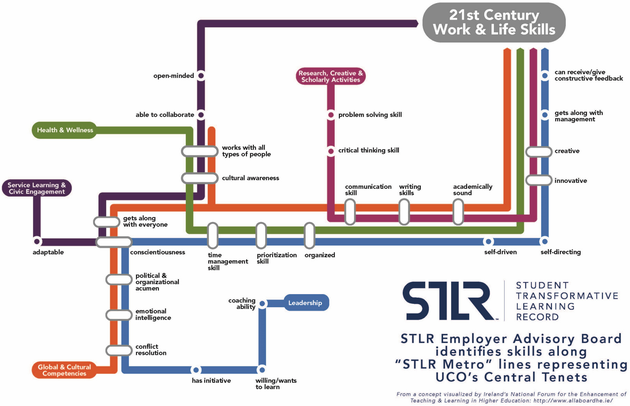

Another way the STLR Employer Advisory Board assisted was by providing the very valuable workforce perspective of what beyond-disciplinary skills needed by employers would be reasonably expected to be developed within each of the Tenets. In an October 2016 working session, the Board developed a list of skills they associated to each Tenet, with some skills being necessarily developed in multiple Tenets. UCO translated that feedback into a ‘STLR Tenets Metro Map,’ shown as in Figure 6:

FIG. 6: STLR Tenets Metro Map

In the Metro Map visualization, discrete skills in each Tenet are represented as individual stops along a Tenet ‘line,’ and Tenet ‘transfer stations’ represent skills the Board thought should be developed as part of development in two or three Tenets.

One final anecdote about STLRized graduates thus far and their impression on employers concerns a Spring 2017 graduate who landed an internship position at an area data analytics firm. Intrigued by the intern’s acumen and abilities, the CEO inquired about the UCO graduate’s college experience, and the graduate shared about STLR. Immediately interested in learning more about STLR, the CEO reached out to UCO for that purpose, reporting that this STLRized graduate is the only intern in the firm’s history who has subsequently been hired, now holding a key position in research as a data scientist.

6. STLR AT OTHER INSTITUTIONS

The compelling associations between STLR and strongly improved retention, as well as improved academic performance as indicated by increased GPA, have caught the attention of other institutions along with higher education organizations. STLR was awarded a 2016 WCET Outstanding Work Award, and has recently received the 2018 American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ Excellence and Innovation Award for Student Success and College Completion. In addition, STLR has been responsible for UCO’s invitation to the 2016 Lumina Foundation-funded/NASPA and AACRAO-led Comprehensive Learning Record project and the 2017–2018 Quality Assurance Commons project on Essential Employability Qualities Certification.

Among other U.S. institutions who have adopted/adapted STLR or are in early stages of doing so is seasoned STLR institution Western Carolina University (WCU), whose version of STLR, named, “DegreePlus,” is located on the co-curricular side of student activity. WCU made DegreePlus a key focus of its institutional re-accreditation; the accreditor, Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), loved the initiative, and re-accreditation was granted at the December 2017 SACSCOC convening.

Among international institutions adopting/adapting STLR is Massey University in New Zealand. From their 2017 Annual Report:

This year we introduced Kahurei (“an adorned cloak”), a unique Massey initiative to facilitate the development of graduates as 21st-century citizens and reflective practitioners by adopting a holistic approach to learning. Students are encouraged to create a ‘kahurei’ or portfolio of academic, work-related and personal experiences, with a particular focus on transferable skills, knowledge and competencies that enhance their employability opportunities. Kahurei focuses on developing five main employability characteristics: self-management, information literacy, global citizenship, exercising leadership, and enterprise. Participating students receive Kahurei transcripts – which serve as Massey University quality-assured records of transferable skills and competencies – complementing the traditional academic transcripts. (Massey University, 2017, p. 28)

For Massey, “Kahurei” is the analog to “STLR,” while “employability characteristics” is the correlate to UCO’s Tenets, and their Kahurei transcripts align to UCO’s STLR CLR.

There are currently STLRized institutions or institutions in early stages (such as with pilots in advance of broader implementation) in Texas, Washington, and North Carolina in the United States, plus Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, and an upcoming U.K. STLR workshop based on multiple institutions’ interest there.

Finally concerning other institutions’ use of and interest in STLR, the Transformative Learning International Collaborative (TLIC) began when international institutions reached out to UCO when seeking universities that had successfully operationalized TL because of their perception that Transformative Learning was necessary as the new pedagogy/andragogy for higher education in the 21st century as the way to ensure graduates capable and motivated to contribute immediately to the social good. One of the South African institutions represented in the Collaborative, for instance, exists within a state in SA where the unemployment rate ranges from 17% to 90%, depending on locality. While TLIC’s focus is broadly on TL, the webinar meetings naturally include discussion about TL’s operationalization, both on TLIC institutions’ campuses and within potential asynchronous professional development opportunities that would be maintained and managed by TLIC.

7. CONCLUSIONS AND LOOKING FORWARD

Two factors seem obvious about STLR regarding this discussion of its efficacy within the online environment: 1) from the faculty standpoint, incorporating STLR within online or hybrid environments is a seamless integration, as STLR’s processes involve use of the Learning Management System as a matter of course, and 2) UCO’s proven successes with STLR’s statistically significant association to better retention and higher GPA as shown in multiple large-N, p < .005 analyses means the institution should expand STLR into more, and potentially all, online classes.

We are undertaking a research project to address why STLR associates with increased retention and improved GPA and also why STLR converts faculty who were late adopters and/or skeptics. Many anecdotal conversations (usually at some point after such faculty have done a STLR project or had at least a couple of STLR assignments in their classes) indicate that STLR has changed faculty thinking. A major theme in such conversations is that 1) before STLR there was no training or support in how to elicit from students the impact the faculty were having on students’ development and lives, and 2) because of the reflective narratives (or other forms of student TL artifacts) students produce, faculty are now able to get a far better student-generated discussion about what is actually going on with the learning in the class and with the realizations that reach beyond course content.

The larger question of “Why does STLR work?” is one that many constituencies, both internal and external to the institution, want answered. Because STLR is not an opt-in experience, the knee-jerk explanation that only ‘good students’ choose STLR is unsupportable. And while it seems quite logical to claim that a big reason for STLR’s success is because of its strong student engagement component, that is something that needs to be tested, especially when considering STLR within an online environment, where student engagement at a distance is very important. Another reason that also seems plausible is that STLR’s (and TL’s, for that matter) requirement of students to reflect on their own learning beyond course content may be an important component in efficacy, given the considerable research showing the benefits of meta-cognition for student success in general.

UCO itself is keenly interested in why STLR works and has underway a mixed-methods research project aimed at answering the question. Preliminary indications are that the answer(s) will apply equally in F2F, online, and hybrid environments.

REFERENCES

Boyer, N.R., Maher, P.A., and Kirkman, S. (2006). Transformative learning in online settings: The use of self-direction, metacognition, and collaborative learning. J. Transform. Edu., 4(4), 335-361. DOI: 10.1177/1541344606295318.

Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Edu. Res. Devel.t, 28(1), 31-44. DOI: 10.1080/07294360802444347.

Christie, M., Carey, M., Robertson, A., and Grainger, P. (2015). Putting transformative learning theory into practice. Austral. J. Adult Learn., 55(1). Retrieved 2018-08-10 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1059138.pdf.

Cranton, P. (1998). Transformative learning: Individual growth and development through critical reflection. In: S. M. Scott, B. Spencer, and A. M. Thomas (Eds.), Learning for life: Canadian readings in adult education (pp. 188–199). Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing Inc.

Dirkx, J. (2001). Images, transformative learning and the work of the soul. Adult Learning, 12(3), 15-16.

Hart Research Associates. (2013). It takes more than a major: Employer priorities for college learning and student success. Washington, D.C.: Hart Research Associates. Retrieved June 14, 2018, from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2013_EmployerSurvey.pdf.

Hart Research Associates. (2015). Falling short? College learning and career success. Washington, D.C.: Hart Research Associates. Retrieved June 14, 2018, from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2015employerstudentsurvey.pdf.

Hart Research Associates. (2018). Fulfilling the American dream: Liberal education and the future of work—Selected findings from online surveys of business executives and hiring managers. Washington, D.C.: Hart Research Associates. Retrieved August 28, 2018, from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2018EmployerResearchReport.pdf.

Henderson, J. (2010). An exploration of transformative learning in the online environment. Paper presented at 26th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning. Madison, WI.

Hoggan, C., Mälkki, K., and Finnegan, F. (2017). Developing the theory of perspective transformation: Continuity, intersubjectivity, and emancipatory praxis. Adult Edu. Quart., 67(1), 48-64.

Jackson, P., and Chakraborty, M. (2014). Transformative learning in the online learning environment: A literature review. University Forum for Human Resource Development. Nottingham, U.K. Retrieved 2018-08-04 from https://www.ufhrd.co.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Porscha-Jackson.pdf.

Keeling, R. P. (Ed.). (2004). Learning reconsidered: A campus-wide focus on the student experience. Washington, DC: NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education and American College Personnel Association.

Keeling, R. P. (Ed.). (2006). Learning reconsidered 2: Implementing a campus-wide focus on the student experience. Washington, DC: American College Personnel Association; Association of College and University Housing Officers–International; Association of College Unions International; National Association for Campus Activities; NACADA: The Global Community for Academic Advising; National Association of Student Personnel Administrators; NIRSA: Leaders in Collegiate Recreation.

Kessler, P. D., and Lund, C. H. (2004). Reflective journaling: Developing an online journal for distance education. Nurse Edu., 29(1), 20-24.

Kitchenham, A. D. (2015). Transformative learning in the academy: Good aspects and missing elements. J. Transform. Learn., 3(1), 13-17.

Massey University. (2017). Massey University annual report 2017. Auckland, Palmerston North, and Wellington, NZ: Massey University. Retrieved June 3, 2018, from https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/fms/About%20Massey/University-Management/documents/annual-report/massey-university-annual-report-2017.pdf?ED32BC3335191A5A35230F1A1D93401B.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Edu. Quart., 28(2), 100–110.

Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow and Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 3-33). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2006). An overview on transformative learning. In P. Sutherland, and J. Crowther (Eds.), Lifelong learning: Concepts and contexts (pp. 24-38). New York: Routledge.

Muncy, J. A. (2014). Blogging for reflection: The use of online journals to engage students in reflective learning. Market. Edu. Rev., 24(2), 101-114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2753/MER1052-8008240202.

Nerstrom, N. (2014). "An Emerging Model for Transformative Learning," Adult Edu. Res. Conf.. http://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2014/papers/55.

Reichlin, L., Eckerson, E., and Gault, B. (2018). Understanding the new college majority: The demographic and financial characteristics of independent students and their postsecondary outcomes. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 19, 2018, from https://iwpr.org/publications/independent-students-new-college-majority/.

Swartz, A. L. and Sprow, K. (2010). Is complexity science embedded in transformative learning? Adult Education Research Conference, Sacramento, CA. http://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2010/papers/73.

Taylor, E. W. (2017). Critical reflection and transformative learning: A critical review. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn., 26, 77-95.

University of Central Oklahoma. (2008). Share Fair 2008: Partnerships in Transformative Learning. Internal UCO document: unpublished.

University of Central Oklahoma. (n.d.). Mission statement. Retrieved June 12, 2018, from https://www.uco.edu/mission-and-vision.

-

Kammer Jenna, A Case Study in the Application of Transformative Learning Theory, in Evidence-Based Faculty Development Through the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL), 2020 Crossref (open in a new tab)

-

Taimur Sadaf, Onuki Motoharu, Mursaleen Huma, Exploring the transformative potential of design thinking pedagogy in hybrid setting: a case study of field exercise course, Japan, Asia Pacific Education Review, 2022 Crossref (open in a new tab)

-

Kammer Jenna, A Case Study in the Application of Transformative Learning Theory, in Research Anthology on Remote Teaching and Learning and the Future of Online Education, 2022 Crossref (open in a new tab)

Comments

Show All Comments