ONLINE ASSESSMENT CHALLENGES DURING THE PANDEMIC: LESSONS LEARNED FROM BANGLADESH FOR THE FUTURE

*Address all correspondence to: Mahammad Abul Hasnat, School of Education, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, E-mail: mahasnat83@gmail.com

In this study, we explored how teachers from Bangladesh experienced challenges with online assessment during the pandemic situation due to COVID-19. An exploratory qualitative study was applied to collect data through semi-structured interviews with six secondary school teachers. This study highlighted the importance of assessment in online classes and guided teachers to find effective online teaching pedagogy to enable student learning. However, the findings of this study showed that due to a lack of prior training and previous experience, teachers found it difficult to assess and give feedback on learning outcomes digitally and ensure students' active participation in the classes. Students' lack of academic honesty was identified as one of the key challenges to ensuring reliability in online assessment. Apart from improving technological advancement, the results of this study suggest that a collaborative working environment between teachers, students, and parents can ensure reliability in online assessment.

KEY WORDS: online assessment, academic dishonesty, COVID-19, Bangladesh

1. INTRODUCTION

The effect of COVID-19 reached every corner as well as every sector in the world. The education sector was directly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and had to shift overnight from a face-to-face teaching/learning approach to online teaching (Pace, 2020). In many cases, teachers had to use unfamiliar technology for the first time in order to support students' learning, which added extra workloads and new challenges (Rapanta et al., 2020). Since students were no longer physically present in a traditional classroom setting, it was particularly challenging for teachers to carry out their teaching without any technical expertise and support (Hodges et al., 2020).

Many educational institutions engage their students in their learning process through online platforms (Mulyanti et al., 2020). Teachers in Bangladesh started their sudden online teaching journey without any training or previous experience (Farhana et al., 2020; Kabir & Hasnat, 2021). Thus, no prior research studies had investigated the effectiveness of online teaching and classroom activities (Al-Amin et al., 2021). In his study, Hwang (2020) suggested introducing formative assessment in the online classroom to offer active learning activities and improve students' learning. However, in their study, Khan et al. (2021) examined the validity, reliability, and fairness of online assessments at public universities in Bangladesh. This was due to the fact that teachers were unfamiliar with the online assessment and students were participating in academic cheating (Farhana et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021).

In this study, we focused on the online assessment practices of secondary school teachers and the challenges they experienced in adopting a relatively new teaching concept during the pandemic. Teachers had to follow different guidelines to adapt to the sudden shift in their teaching strategy to an online platform with numerous limitations. During the pandemic, assessment practices were quite difficult to implement in online classes (Al-Amin et al., 2021). With regard to this issue, it was very difficult for the teachers to identify reliable online formative assessment strategies. In addition, there were limited or no instructional designs in place for assessment during the pandemic (Sutadji et al., 2021). Moreover, teachers in Bangladesh had no past experience in implementing online formative assessment (Ministry of Education, 2020). Different studies have been conducted worldwide, including in Bangladesh, over the last few years to investigate the various aspects related to online teaching and learning. However, the proper guidelines for online formative assessment still remains an unexplored area. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to offer a broader picture to secondary teachers in Bangladesh on formative assessment from the reflections of six veteran teachers who experienced challenges and overcame them in order to continue their online teaching. We also explored online assessment challenges. To offer a comprehensive understanding, we investigated the online teaching and learning experiences of teachers. Specifically, we delved into their experiences related to assessment practices during the pandemic.

1.1 Secondary Education in Bangladesh

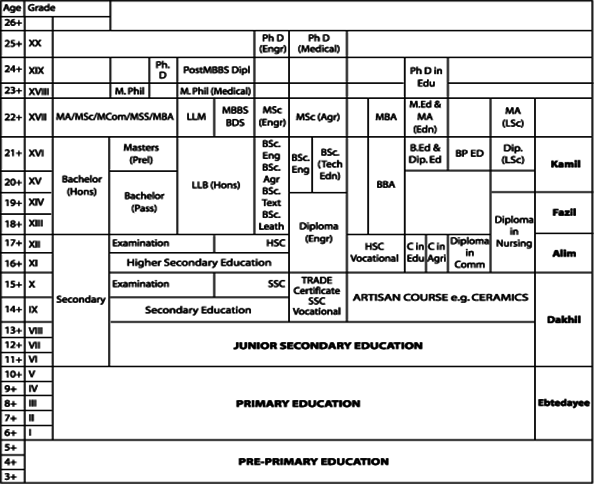

Since the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, there have been three separate streams in the education system running parallel to one another. Students are free to choose any one of them. The mainstream type is the Bangla medium secular education system. Another medium type is Madrasah, which is the traditional education system taught in religious schools. The third education stream is the English medium system, which is designed to align with the British education system (Kabir, 2020). The schools of this medium type conduct classes and exams but send students' work to England or the British Council in Dhaka for the evaluation process (Mousumi & Kusakabe, 2017a,b). Figure 1 shows the stages and clusters in the Bangladesh education system.

FIG. 1: The structure of the education system (adapted from the Ministry of Education, 2010)

1.2 Literature Review

Due to the impact of COVID-19, teachers adopted entirely new teaching and learning approaches (König et al., 2020) to connect with students and continue students' learning. Teachers used asynchronous and synchronous approaches in their teaching techniques due to the immediate shift to online teaching in order to facilitate student learning and assessment (Moorhouse & Wong, 2022). In the synchronous teaching approach, teachers and students schedule specific times to discuss, interact, and address learning difficulties through video conference, live chatting via Zoom meeting, or Google Meets (Rigo & Mikus, 2021; Khotimah, 2020). Both asynchronous and synchronous modes of online teaching were found to be supportive of the students' learning (Moorhouse & Wong, 2022). However, teachers faced challenges in implementing online assessments (Abduh, 2021) and identified online exams as major areas needing improvement (Maraqa et al., 2022). As a result, it is important to conduct further studies in order to identify more effective techniques to overcome the challenges of implementing online assessments of students learning (Vonderwell et al., 2014).

Assessment, in both face-to-face and online platforms, is considered an essential part of the teaching and learning process (Maki & Shea, 2021) because the result of assessment practice allows teachers to evaluate and guide them in improving the quality of learning. It is a continuous activity or practice that determines the various forms of teaching and learning approaches teachers utilize in the classroom (Nurfiquah & Yusuf, 2021). A teacher often applies formative assessment to evaluate students' understanding of a particular topic, their progress, and their learning needs in classroom teaching (Karimi & Shafiee, 2014). Jacob and Issac (2005) found that assessment provides an opportunity for teachers to check students' learning abilities and change their teaching techniques to offer immediate feedback continuously to students on a specific topic. Findings from different studies have shown the usefulness of different techniques applied to online assessment. Gikandi et al. (2011) identified various techniques for formative assessment in their systematic qualitative review of the research literature with respect to various online tools such as test quiz tools, discussion forums, self-reflection, and e-portfolios. Ogange et al. (2018) suggested different tools based on students' experiences that included multiple-choice questions (MCQs), matching, true/false questions, fill-in-the-blanks, e-portfolio, and wikis for assessment in online teaching. Teachers in Bangladesh assessed students from the feedback of given home assignments and homework (Farhana et al., 2020).

Assessment-centered feedback from an efficient formative online assessment platform can foster both teachers and learners in meaningful engagement with various learning experiences (Gikandi et al., 2011) and enhance students' dedication to esteemed learning experiences (Baleni, 2015). However, Gikandi et al. (2011) identified the challenges in ensuring the validity and reliability of formative assessments in online platforms. Hodgson and Pang (2012) conducted a study on online formative assessment activities for 10 weeks, where they found students expressed high satisfaction with the process and increased their commitment to finding answers to any problem with their peers. Conversely, teachers' preparedness and sudden shift to online formative assessment practice can lead to different results. For example, Engzell et al. (2020) found that the progress in students' learning was minimal or sometimes insignificant during their stay at home during the pandemic lockdown. On the other hand, studies have shown that identifying students' specific setbacks in their work by teachers and providing guidelines to correct them through formative assessment can produce predominantly good results even with low performers (Baleni, 2015).

Implementation of assessment has always been challenging in both face-to-face and online teaching contexts. Nurfiquah and Yusuf (2021) found that teachers were not ready for the sudden transition from face-to-face to online teaching and were not optimistic about assessment approaches to identify students' success and ensure active participation in online teaching. Similarly, Al-Mofti (2020) found teachers had insufficient knowledge of how to effectively implement appropriate strategies and lacked the ability to create assessment criteria that focused on topic and learning activities. Thus, teachers' lack of understanding with respect to remoting assessing students is one of the major challenges they face in online teaching platforms (Khan et al., 2021). In addition, ensuring the validity, reliability, and fairness in online assessment during the pandemic was a common problem. Academic dishonesty was identified as one of the major problems in validating unsupervised online assessments during COVID-19 (Lee et al., 2021). Guangul et al. (2020) identified several challenges in remote assessment. Among the challenges (infrastructural, commitment and learning outcomes), academic dishonesty was the main challenge. It is hard to offer validity and reliability in online assessments due to academic dishonesty, which results in achieving unexpected grades (Arnold, 2016). As a result, cheating created blocks and resulted in negative output in online assessments during the pandemic situation (Khan et al., 2021).

1.3 Research Questions

This study was conducted to explore teachers' first-hand experiences with formative online assessment and the challenges they faced practicing in newly adopted online platforms during the pandemic. This objective gave rise to the following research questions:

- What were the challenges faced by teachers in assessing student learning while teaching online during the pandemic?

- How did the teachers deal with the assessment challenges while teaching online during the pandemic?

2. METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted to identify teachers' experiences and challenges faced in dealing with online formative assessments. A qualitative research design was used, which followed the exploratory research method to collect in-depth data through semi-structured interviews. Researchers often use the exploratory research method to gain a more in-depth understanding of a group of people's activity in a specific situation (Given, 2008). Swedberg (2020) defined exploratory research as an attempt to discover something new. Given (2008) stated that researchers use exploratory research to explore particular people and their activities when there is limited knowledge. Online formative assessment experiences by Bangladeshi school teachers during the sudden pandemic situation are important to be explored.

2.1 Participants

We interviewed six teachers in this study from secondary schools using purposive sampling that involved a deliberate and nonrandom selection process, in which we intentionally sought individuals possessing particular characteristics (Johnson & Christensen, 2014). Prospective psrticipents were sent consent forms before starting the interview, in which they were assured that all of the data would only be used for this study. The teachers were interviewed one-on-one via Zoom, and the duration of the interview with each teacher was 20–25 minutes. Our interviews with the participants were recorded with the full consent of the participants. We conducted all of the interviews in Bangla† considering the preferences of the participants. All of the participants in this study were selected randomly from a secondary school. The school is located in an urban area and is a well-known, private, co-educational school. Approximately 1100 students are in the school in grades 9–12. As participants, the teachers were selected from this school in order to understand what strategies they applied to online formative assessment and what challenges they experienced in assessing students' learning achievements. This key theme led us to select our participant selection criteria: (a) online teaching experience from the beginning of the school closure; (b) experience in formative assessment in both face-to-face and online teaching; and (c) willingness to be part of this study. All of the participating teachers were given pseudonyms (T1–T6) to maintain confidentiality. The selected teachers were experienced teachers who taught at the secondary level for more than 15 years.

Since the interviews were semi-structured, the participants were asked open-ended questions at the beginning of the interviews (Table 1). We listened to our recorded Zoom interviews several times to identify potential areas related to answering our research questions. Then, we transcribed those areas in Bangla and translated them into English. Both Bangla and English written translations were sent to the respective teachers to check the correctness and exact meaning of their interview. We analyzed all of the findings thematically after getting the translated interviews back from the participants. Thematic analysis in qualitative research is considered a flexible and accessible method that is employed to analyze data (Braun & Clarke, 2012) and gives researchers the ability to identify key findings related to a study's specific research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

TABLE 1: Semi-structured questions

| Question Number | Semi-Structured Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | How have you conducted an online assessment during the pandemic? |

| 2 | In conducting online assessments, what are the challenges you have faced and how did you overcome them? |

| 3 | Do you think online assessments are reliable? What are your thoughts on this issue? |

3. FINDINGS

3.1 Findings on Assessment Practice

In this study, we aimed to identify the assessment challenges teachers' experienced in online classes. We investigated the initial experiences teachers had as they shifted to online teaching. Teachers were aware of the COVID-19 situation and knew there would be a gap in their students' performance during the crisis compared to the normal classroom situation. As a result, teachers avoided giving high-stakes exams and instead placed emphasis on formative assessment.

3.1.1 Assessment Practices in Pre-Recorded Classes

As discussed previously in detail, the first teaching strategy employed by the teachers was to give students video recordings of class lessons. It was an ambitious initiative at a time when teachers, students, and parents were anxious and the overall situation in Bangladesh was uncertain. Therefore, this initiative was appropriate since it allowed students to continue their classes and reduced their worries about educational uncertainty. All of the teachers made recordings and followed pre-recorded classes to discuss topics and assess students' learning. At the end of the class, teachers provided the students with a few homework questions and instructed the students to complete the task and then send a photograph of the completed homework to the teachers via messenger. The teachers then returned those copies to the students with feedback and comments.

The teachers did their best to make the pre-recorded lessons easy to understand and engaging for the students. However, the teachers identified a common problem after checking students' homework and realized that students were completing homework without watching the full recorded class. There was a disconnection between the teachers' lectures and the students' writing in their homework. According to T1:

Anyone can watch a recorded class (students, parents, relatives, my colleagues, and authority), as a result, I spent more time for preparation to offer a class with zero error to the students. However, I couldn't check whether students were watching recorded classes or not. I couldn't see any reflection in their homework writing from the discussion of my recorded class. They prepared their homework without following my discussion and guidelines.

T5 pointed out a similar problem that he identified and shared:

After a few days continuing of my recorded class, I realized that students were not watching my recorded class and watching only the homework part to submit. Also, I found good quality writing in their homework but a word-for-word from the textbook which mismatched with my guidelines in the recorded class.

T4 highlighted another limitation in the pre-recorded class:

Pre-recorded class was one way where a teacher could deliver the topic and was not possible for me to confirm that students were receiving. It was not possible to confirm whether they watched my recorded class or not. I couldn't make watching the class recording class obligatory for the students to watch. It depended on the student's self-interest.

The comment by T1 highlighted the importance of assessment and feedback in the teaching/learning process. He was not happy and pointed out that the pre-recorded class was less effective because proper assessment and feedback were missing. In addition, he was not motivated by the student's performance in the way he prepared a recorded class. Similarly, T5 highlighted the reduced chance to verify students' attendance in the recorded classes. He also raised questions about the reliability of the students' homework since they tended to copy from the textbook without following the teachers' discussions or guidance from the recorded class. The students' tendency to copy directly from the textbook blocked their creativity and did not allow them to effectively achieve the learning objectives. T4 pointed to the limitations of interacting with the students, thus decreasing the opportunity to evaluate their progress. Not all students are motivated to study on their own without output from an assessment or evaluation process. Common wisdom in teaching says if you want students to do something, it has to be assessed in some way; this process was missing in the recorded classes (Wiliam, 2011).

3.1.2 Live Class on Zoom

The teachers clearly indicated that pre-recorded lessons did not work well. Thus, all of the teachers decided to begin live classes on Zoom, an internet-conferencing software platform, to overcome the challenges they faced in pre-recorded classes and offer a more effective teaching/learning approach. It was a huge task for the teachers to introduce Zoom to all of the students and parents. They trained them over the phone since lockdown was declared throughout Bangladesh and face-to-face meetings were not allowed. Within a short period of time, the teachers were able to connect with the students on Zoom and continue their live classes. However, they still faced different challenges in the teaching/learning process. T2 shared that:

I find a problem with students' attentiveness in the Zoom live classes. I cannot see my students when I share any slides or documents on my screen to discuss. Also, it is difficult to monitor all students' camera and their activities while discussing any topic. It is not possible in the face-to-face class.

To check students' learning from previous lessons, teachers asked a few questions at the beginning of the live class and provided feedback if needed. In addition, they asked short questions to check students' understanding and attentiveness. Teachers identified a few problems with students' fair responses. T3 found that:

Students are supposed to answer questions from memorization or their understanding. However, it is hard for me to check whether a student is answering by reading from a textbook or not. But, I can realize that students' eyes are moving back and forth, watching something. I can't help stopping them. Students' body language indicates whether students are prepared or not. It is not possible to measure in the virtual classroom.

T4 added that:

Without proper preparation, students have the tendency to claim that they are prepared and answer by seeing the textbook hiding from the camera. Low-performing students are achieving top scores on class tests by utilizing books to assist them in preparing and submitting their homework. Intentionally, I ask the same question from the class test orally, and in most cases, they are unable to reply correctly.

T6 shared that:

Students easily can avoid answering any question. For example, students often say, I can't hear you and don't understand what you are saying. I am facing a problem with my network connection. I received different types of excuses from the students.

T1 shared an interesting experience:

One day I noticed that one of my students suddenly froze herself while answering to prove that her net was not working. But her ceiling fan and curtains were moving. It means it was not her internet problem. She became normal and admitted that she was not prepared.

Keeping students attentive and ensuring fairness in Zoom classes was also a big challenge for teachers. Teachers often shared different slides on their screens and could not see the students' cameras and movements. T2 shared that, “students always take the chance to be busy with other work when they realize that the teacher is not watching them and students easily shift their mind from lecture to other activities.” T3 claimed that:

Live classes on Zoom also cannot ensure students' fairness in assessing their learning. Students often could not answer a question in their own words, indicating that they had not learned the lesson properly. Students easily can answer any question without any prior preparation to show their learning outcomes. They can cheat by reading from the book when teachers try to assess students' previous lessons.

Similarly, T4 shared that, “students claimed that they learned the previous lesson as they could answer from the book.” He also identified and suspected cheating because low-performing students were getting good marks in their class tests. The comment by T6 suggests that students could easily avoid answering questions in the classes if they were not prepared by blaming the internet connection.

3.1.3 Assessment for Improving Teaching Techniques

The concept of online teaching was relatively new for all of the teachers. Therefore, it was important for them to improve their teaching techniques to accommodate online teaching. However, realization or motivation was missing for the teachers to improve their online pedagogical knowledge. T3 addressed one of the key issues that was missing in the pre-recorded classes. He shared that:

It was not possible for me to check students' performance due to limited opportunities for students' assessment. I do believe that students' performance acts as a mirror for me to judge my teaching technique. By assessing students' performance I can assess both my students' learning as well as my own performance. This opportunity allows me to take further initiative to improve myself. However, as a teacher, pre-recorded classes did not allow me to assess students' learning and improve my teaching techniques.

T6 shared a similar experience:

I don't think we can achieve all learning outcomes through pre-recorded classes. Because I can't judge my students, interact with them, or exchange our views. As a result, without assessing my students' performance it was difficult for me to claim my teaching technique was effective for students' learning.

T2's experience was similar to the two previous comments, which pointed out that the pre-recorded classes limited intearctions with the students, making it difficult to check their level of understanding of the lessons being taught:

It is not possible to get feedback and measure students understanding in the pre-recorded class. It's absolutely a one-way process. As a result, after discussing with my other colleagues, we decided to start online classes through the Zoom application to check students' understanding of pre-recorded class and fill the learning gap.

From the previous comments by the teachers, it is clear that the pre-recorded class is a one-way process, where teachers actively deliver their lectures, students passively listen, and class participation is not possible. T3 reflected that due to limited assessment opportunities he was not able to judge his teaching technique and acertain whether or not it was effective for the students. In addition, it was not possible for him to identify his baseline performance to improve his teaching technique to the next level. Students' interactions and assessment were missing in the pre-recorded class, such that proper feedback could not be provided to the students. As a result, T6 pointed out that he was unable to understand students' difficulties and explain this in more detail. By his previous comment, he concluded that students may not be able to understand and learn almost everything by watching a recorded class and sometimes students may need more clarification for in-depth learning. T2 identified the barriers in the pre-recorded class and reflected on the importance of students' interactions, assessment of students' learning, and feedback to the students. The teachers introduced live classes through the Zoom application since they realized the importance of assessment and interaction with the students. However, they concluded that the pre-recorded lessons did not work; online in-person lessons via Zoom were better than the pre-recorded lessons, but not by much.

3.2 Issue of Reliability

The reliability issue was identified due to students adopting unethical academic practices while they were assessed. According to Hughes (2014), “Reliability is a measure of how consistent an assessment process is” (p. 3). For example, if variations in the test, time, and setting do not change the outcome of the test-taker's performance and the results remain the same or are almost similar, then the test results can be identified as reliable.

3.2.1 Introducing Different Assessment Techniques

Considering the pandemic situation, the teachers decided to administer spot tests or surprise tests with new techniques to ensure fair online assessment. As a result, they decided to employ the Google Forms software platform to deliver MCQs and a new question pattern for written questions. They introduced a Google form for MCQs from the previous lesson, which included 15 or 20 questions and allowed the students one minute to answer each question. Students had to submit their answers within the time frame and they could not submit the answer script if the time was over. T4 shared his observation:

I observed that students were attentive and serious about participating in exams on Google Forms. Firstly, it was new for them and they were more curious. Because of time obligations, they couldn't spend time taking help from any source, and time limitations forced them to be focused on their exam.

T5 stated that:

I introduced a class test where students were asked to turn on their cameras all the time while writing answers and taking photos of their answer scripts and send them to my messenger ID within 15 minutes after exam time duration.

T6 added that:

I changed written types of question papers where students were unable to find answers directly from the textbook or any other sources. My prepared question paper allowed students to be creative in their writing. As a result, they started focusing on writing rather than searching for any source.

However, applying the aforementioned techniques to online assessment was also challenging to ensure reliability. T1 observed that, “We do not have any control over students. Students were instructed to keep their microphones off to reduce household and surrounding noises. That allows students to communicate with their friends with another device.” T3 added that:

Most of the students attended their classes and exams through mobile devices. Few students can divide their mobile screen into two parts—one part for Zoom attendance and another part for searching for answers and sharing textbooks to answer. They can look at the mobile device and essentially cheat. It is difficult to determine whether students are answering truthfully.

T5 shared that:

I came to know that students created a Messenger Group for chatting to find the correct answer in the exam. Students immediately started their chatting to aid collusion in determining answers to questions through the Messenger Group. Sometimes they assigned other students to find specific answers. As I shared with you we (the school authority) opened a Messenger Group for communicating with the students, so students sometimes by mistake send their texts to our school Messenger Group. Students admitted their unethical practices when I asked them to refer to their text.

T2 brought different experiences:

Parental support in the home setting did not allow us to ensure fair assessment online. I experienced several times that parents are trying to help their children through online means. I had to tell them please don't support anyone, let them write from their understanding.

T1 disappointingly added that:

Few parents really don't want to support their children during exams and who really can't support them. They complained about the parents who supported their children in the exam. It was really difficult for me to convince both types of parents.

From the aforementioned findings, it is clear that giving students limited time to answer questions played a positive role in ensuring effective assessment. T5 and T6 introduced creative question patterns in the written test, where students were unable to find any answer directly from any sources that were available for the students. In addition, they were unable to take extra time after the exam since they were instructed to immediately submit photographs of their answer scripts.

Conversely, T5 shared how students demonstrated that his innovative assessment technique was not reliable since the students created a Messenger Group to find answers by communicating with other friends. Similarly, T2 and T1 found the level of parental cooperation disappointing, which created a big question mark on reliability issues in online assessment in a home setting. In this regard, parents could be a source of trust to ensure reliability issues. The statements highlight that the teachers could not find a satisfactory and effective means of assessing student learning in the online space. However, they were hopeful that in the future something will become available to do this job.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings from the previous data unfolded the following key themes: (a) the importance of formative assessment in online teaching; (b) students' involvement in academic dishonesty created barriers to checking students' learning and ensuring reliability in online assessments; and (c) the lack of the teachers' training and readiness and the lack of support from parents made it difficult to implement online assessment in the home setting.

4.1 Importance of Online Assessment

During the pandemic, teachers in Bangladesh introduced both pre-recorded and live Zoom classes in order to find better teaching practices for their students such that the students could remain connected with their education. These two approaches were relatively new concepts for teachers within the Bangladeshi context and gave them the opportunity to explore new ways of engaging students, interacting with them, and providing feedback through assessment. Teachers continuously applied different assessment techniques to assess students, in which their decisions were based on their own reflections (Zhang et al., 2021).

Based on the experiences of the teachers, teaching through pre-recorded classes was less effective since it was a one-way process with limited opportunity to interact and provide feedback to the students. Interaction with the students was not possible through this teaching technique and students were not self-motivated to watch and follow lectures. Research has suggested that a combination of assessment and feedback through interaction supports students' learning (Guangul et al., 2020). Lack of interaction in recorded classes makes students feel alone and frustrated (Khotimah, 2020).

The opportunities for teachers to interact with students during classroom activities through online teaching are limited (Al-Amin, et al., 2021). Since teachers were unable to interact with students and check their learning, they also did not have the opportunity to evaluate their own teaching strategy. Thus, teachers were not sure if their newly adopted online teaching methods were effective with the students. Pre-recorded teaching techniques did not allow teachers to improve their online teaching pedagogy. Given the situation, teachers introduced live online teaching through Zoom to interact with the students and provide feedback. This approach brought different challenges for the teachers with limited opportunities to interact with the students. Keeping students attentive in the Zoom class was significantly difficult for the teachers since students always came up with different reasons or excuses. Students often claimed that they were fully prepared for their previous lesson. However, in most cases, they either replied by reading from the textbook or taking help from any other resources, or they stopped answering in the middle blaming a poor internet connection. Similarly, Panday (2020) noticed that students remained silent when a teacher asked them any question. This showed that instant feedback during a class was also difficult using this approach; learning during the pandemic was as hard for the students as it was for the teachers (Guangul et al., 2020).

Research has suggested that interaction in the classroom and feedback allow teachers to get a clear idea of required pedagogical changes in classroom practice (Black & Wiliam, 2005). At the same time, teachers can adopt new teaching strategies to offer better learning opportunities for students by determining students' competency and learning gaps through assessment and interaction in classroom teaching (Guangul et al., 2020). This reflects the importance of online assessment in order to improve teachers' pedagogical methods and check students' learning outcomes (Perera-Diltz & Moe, 2014).

4.2 Students' Involvement in Academic Dishonesty

Teachers also faced problems delivering written tests and applying different techniques to ensure reliability in the online assessment. Initially, teachers found effective online assessment through Google Forms and creative question patterns for creative writing compared with other options. However, this solution did not ensure effective online assessment practices since the teachers identified misuse of technology by the students, which they could not control. Students were able to communicate with their friends or browse different sources to find answers.

Academic dishonesty and students' lack of commitment to answering questions and submitting their homework were identified as some of the main challenges in online assessment. It was difficult for the teachers to identify students' learning gaps and take the necessary steps to reduce these gaps accordingly. As a result, online assessment in the classroom practice was found to be one of the most difficult tasks for the teachers (Al-Amin et al., 2021). Students often took the opportunity to negatively misuse technological advancements. Students easily avoided answering short questions by claiming the internet was not working, making it difficult for teachers to check the students' learning gap during the class and provide feedback to confirm the lesson. The teachers tried multiple techniques to assess student learning. However, whatever method the teachers tried the students quickly found a way around it, making it seem like they had learned the lesson when it was plain to the teacher that this was not true.

Online assessment required appropriate home environments to ensure reliability; however, teachers also failed to ensure this since they did not always obtain adequate support from parents. This was not necessarily the teachers' fault. They were working in a very new and very difficult environment. There may be other factors, but it shows that parents wanted to see higher grades from their children on exams, especially with respect to societal pressure regarding the high-stakes exams in the Bangladesh education system (Amin & Greenwood, 2018). Thus, both parents and students wanted high grades or marks on exams, regardless of how they were achieved.

Reliability is a mandatory factor in assessments such as tests. If the consistency of test scores does not comply with different times and settings, we cannot be assured that the assessment accurately measures student ability (Kabir, 2018). To minimize academic dishonesty in online assessments, Guangul et al. (2020) suggested applying different techniques such as online report submission, different questions for individual students, and online presentations to check students' understanding. Applying both trustworthiness to ongoing summative assessment and interactive formative feedback may ensure students' learning and minimize academic dishonesty (Baleni, 2015). Besides another technological advancement to ensure reliability, we suggest addressing a few challenges that arose from the findings of our study.

The findings of this study showed that online assessment was relatively new for the students, but they easily adopted different techniques to participate in the assessment process. It appeared that their efforts to engage in academic dishonesty (cheating) were rather clever and innovative. We can divert students from this type of activity in a positive way. That result revealed that students actively worked to find answers through their Messenger Group, which indicated that group work and shared learning opportunities is possible in online teaching and assessment. A group problem-solving task could be applied to minimize dishonesty (Pedersen et al., 2012). However, Bangladesh is not in such a position to adopt any new technology immediately since the necessary tools may not all be free of cost and someone will need to pay the extra cost to apply for online assessment. In addition, technological limitations may not allow some students from non-urban areas easy access to effective technological tools (Al-Amin et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2021).

4.3 Lack of Teacher Training and Less Support from the Parents

Teachers' lack of training and prior experience with respect to online teaching platforms prevented them from taking innovative initiatives or steps to overcome challenges and improve online assessment practices. They were not ready for the overall online teaching, learning, and assessment process. As a result, they spent most of the time continuing the online teaching and assessment rather than improving overall practice. Assessment techniques in online teaching depend on an appropriate plan that can be executed accordingly in practice (Al-Maqbali & Hussain, 2022). However, the findings of our study showed that teachers were not well-trained and had to improvise their methods to find better techniques without having a plan in place (Xu, 2017). Therefore, it is important to address teachers' limitations related to implemently online assessment techniques and ensuring reliability, and to organize training of appropriate tools and techniques to assess students' learning (Khan et al., 2021) in order to minimize academic dishonesty. Moreover, teachers need to keep themselves updated regarding student's activities and involvement in academic cheating by building rapport with the students and parents. Teachers can change their assessment technique from a direct to an indirect approach to check students' learning.

A collaborative working partnership between parents and teachers is needed to ensure the reliability of online assessment. Some studies have shown that parents supported home learning during the pandemic to continue their children's learning (Bhamani et al., 2020). However, our findings showed that parents were less supportive of implementing reliable online assessments. On the other hand, in a few cases, parents supported their children's involvement in cheating while attending the online assessment process. Parental attitudes sometimes pressured students to please their parents and engage in cheating (Sarita & Dahiya, 2015). This reflects the importance of parents' support in minimizing academic cheating and ensuring reliability in online assessment. Nevertheless, in Bangladesh, there has not been a concerted effort to foster collaboration between parents and teachers to effectively address the issue of academic dishonesty among students in online assessments. Therefore, to enhance student performance, it is essential to reduce the distance between teachers and parents, promoting a collaborative environment that encourages joint efforts (Hasnat, 2016).

Research findings from different contexts have suggested applying various techniques to ensure reliability and minimize academic dishonesty. For example, the sources include reflective journals and wikis assessment tools for group assessment and collaborative learning (Perera-Diltz & Moe, 2014), different question papers for individual students and reports submitted with presentations (Guangul et al., 2020), paper writing with case studies, and online discussions with peer assessment (Sutadji et al., 2021). There may be different suggestions to minimize academic dishonesty. However, technological advancements may not necessarily minimize academic dishonesty (Pedersen et al., 2012); students may continue to cheat by finding new methods or updating their current strategies. Moreover, all of the research findings that suggested different applications to minimize academic cheating were from higher education systems; there is limited research studies available on cheating at the secondary school level. Thus, in this study we emphasized working on teachers' preparation through appropriate training, improving students' integrity, and getting support from parents by minimizing the high-stakes exam system. Further intensive research needs to be conducted to identify compatibility and readiness for online assessment in the context of Bangladesh.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study reveal the challenges related to online assessment, including the reliability of assessments, issues related to cheating, maintaining the integrity of the assessment process, addressing technical difficulties, providing equitable access for all students, and effectively evaluating and grading student performance in a digital environment. This study also revealed the importance of online feedback in real time, which plays an important role in determining appropriate teaching strategies to engage students and enhance their learning. Immediate feedback and formative assessment can enhance the effectiveness of online teaching and guide teachers to find appropriate teaching techniques. However, appropriate online feedback tools to ensure the reliability of teachers' online assessments currently do not exist in Bangladesh. At the same time, this study showed that both students and parents failed to prove their honesty in online assessment practices. The unique circumstances and pressures faced by parents and teachers during the pandemic are the probable reasons behind their involvement in dishonest practices during online assessments. We acknowledge the urgency that may have necessitated their engagement in such activities; however, ensuring reliability in online assessment remains challenging. The nature of these challenges may vary from one context to another due to different education systems, teachers' online assessment competencies, stakeholder preparation, technological capacity, and support from the school administration and government.

In conclusion, we provide actionable recommendations. We suggest that educators and policymakers should design and contextualize online assessment techniques, emphasizing the need for stakeholder readiness. In addition, a long-term action plan should be in place to enhance technological and pedagogical advancements and integrate online assessments that ensure reliability in the COVID era. Since the pandemic, for a variety of reasons, online teaching and learning have become a parallel reality, existing alongside the on-campus educational mode. Therefore, educational institutions are now rethinking their teaching and learning environment, making every effort to use online learning facilities, even within this context of new financial, technological, and pedagogical limitations.

The authors hope that this investigation will lead to the development of teacher education programs that assist educators in handling challenges stemming from any future natural disasters or situations akin to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors also suggest that 21st century teachers should be given training in modern digital educational methods such that they can enhance their online assessment literacies for online classes during the post-pandemic era. Thus, the results of this study give us a forward-looking perspective that focuses on the future of online education, including advancements in assessment security technologies, adaptive and interactive assessment methods, artificial intelligence (AI) integration, and the need for accessibility and inclusivity.

Regarding further research, the authors assume that the future of online challenges in education is likely to involve advancements in assessment security technologies in order to prevent cheating. It is also likely that it will involve the development of more adaptive and interactive assessment methods, the integration of AI for personalized feedback, increased focus on accessibility and inclusivity in online assessments, and the continued evolution of remote proctoring techniques.

REFERENCES

Abduh, M. Y. M. (2021). Full-time online assessment during COVID-19 lockdown: EFL Teachers' Perceptions. Asian EFL Journal Research Articles, 28(1), 26–46.

Al-Amin, M., Zubayer, A. A., Deb, B., & Hasan, M. (2021). Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh: Students' response on preparedness, participation and classroom activities. Heliyon, 7(1), 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05943

Al-Maqbali, A. H., & Hussain, R. M. R. (2022). The impact of online assessment challenges on assessment principles during COVID-19 in Oman. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 19(2), 73–92.

https://doi.org/10.53761/1.19.2.6

Al-Mofti, K. W. H. (2020). Challenges of implementing formative assessment by Iraqi EFL instructors at university level. Koya University Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (KUJHSS), 3(1), 181–189.

Amin, M. A., & Greenwood, J. (2018). The examination system in Bangladesh and its impact: On curriculum, students, teachers and society. Language Testing in Asia, 8(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-018-0060-9

Arnold, I. J. M. (2016). Cheating at online formative tests: Does it pay off? The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.02.001

Baleni, Z. G. (2015). Online formative assessment in higher education: Its pros and cons. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 13(4), 228–236. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1062122.pdf

Bhamani, S., Makhdoom, A. Z., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N., Kaleem, S., & Ahmed, D. (2020). Home learning in times of COVID: Experience of parents. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 7(1), 9–26.

DOI: 10.22555/joeed.v7i1.3260

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2005). Changing teaching through formative assessment: Research and practice, The King's-Medway-Oxfordshire Formative Assessment Project. In Formative assessment: Improving learning in secondary classrooms. OECD Publishing.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2020). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. SocArXev Papers. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/ve4z7

Farhana, Z., Tanni, S. A., Shabnam, S., & Chowdhury, S. A. (2020). Secondary education during lockdown situation due to COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: Teachers' response on online classes. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(20), 97–102. DOI: 10.7176/JEP/11-20-11

Gikandi, J. W., Morrow, D., & Davis, N. E. (2011). Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the literature. Computers & Education, 57, 2333–2351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.004

Given, L. M. (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage.

Guangul, F. M., Suhail, A. H., Khalit, M. I., & Khidhir, B. A. (2020). Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(4), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09340-w

Hasnat, M. A. (2016). Parents' perception of their involvement in schooling activities: A case study from rural secondary schools in Bangladesh. Studia Paedagogica, 21(4), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2016-4-7

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Hodgson, P., & Pang, M. Y. C. (2012) Effective formative e-assessment of student learning: A study on a statistics course. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(2), 215–225.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.523818

Hughes, A. (2014). Testing for language teachers (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Hwang, C. S. (2020). Using continuous student feedback to course-correct during COVID-19 for a nonmajors chemistry course. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 3400–3405.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00808

Jacob, S. M., & Issac, B. (2005). Formative assessment and its elementary implementation. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education (ICE 2005), National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2014). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Kabir, S. M. A. (2018). IELTS writing test: Improving cardinal test criteria for the Bangladeshi context. Journal of NELTA, 23(1–2), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.3126/nelta.v23i1-2.23352

Kabir, S. M. A. (2020). Listen up or lose out! Policy and practice of listening skill in English language education in Bangladesh [Doctoral thesis, University of Canterbury]. UC Research Repository.

http://dx.doi.org/10.26021/1100

Kabir, S. M. A., & Hasnat, M. A. (2021). Teachers' reflection on online classes during and after the COVID-19 crisis: An empirical study. International Journal on Innovations in Online Education, 5(3), 23–41.

DOI: 10.1615/IntJInnovOnlineEdu.2021039032

Karimi, M., & Shafiee, Z. (2014). Iranian EFL teachers' perceptions of dynamic assessment: Exploring the role of education and length of service. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(8), 143–162.

https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n8.10

Khan, R., Basu, B. L., Bashir, A., & Uddin, M. E. (2021). Online instruction during COVID-19 at public universities in Bangladesh: Teacher and student voices. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (TESL-EJ), 25(1), 1–27. https://tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej97/a19.pdf

Khotimah, K. (2020). Exploring online learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Arts and Humanities (IJCAH 2020), 491(Ijcah), 68–72.

https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.201201.012

König, J., Jager-Biela, D. J., & Glutsch, N. (2020) Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650

Lee, J., Kim, R. J., Park, S-Y., & Henning, M. A. (2021). Using technologies to prevent cheating in remote assessments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Dental Education, 85(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12350

Maki, P. L., & Shea, P. (Eds.). (2021). Transforming digital learning and assessment: A guide to available and emerging practices and building institutional consensus. Routledge.

Maraqa, M. A., Hamouda, M., El-Hassan, H., El-Dieb, A. S., & Aly Hassan, A. (2022). Transitioning to online learning amid COVID-19: Perspectives in a civil engineering program. Online Learning, 26(3), 169–201.

https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v26i3.2616

Ministry of Education. (2010). National education policy. Ministry of Education, People's Republic of Bangladesh.

https://moedu.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/moedu.portal.gov.bd/page/ad5cfca5_9b1e_4c0c_a4eb_fb1ded9e2fe5/National%20Education%20Policy-English%20corrected%20_2_.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2020). Education sector COVID-19 response and recovery plan. Ministry of Education, People's Republic of Bangladesh.

Moorhouse, B. L., & Wong, K. M. (2022). Blending asynchronous and synchronous digital technologies and instructional approaches to facilitate remote learning. Journal of Computers in Education, 9, 51–70.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00195-8

Mousumi, M.A., & Kusakabe, T. (2017a). Proliferating English-medium schools in Bangladesh and their educational significance among the “clientele.” Journal of International Development and Cooperation, 23(1–2), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.15027/42488

Mousumi, M. A., & Kusakabe, T. (2017b). The dynamics of supply and demand chain of English-medium schools in Bangladesh. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 15(5), 679–693.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2016.1223537

Mulyanti, B., Purnama, W., & Pawinanto, R. E. (2020). Distance learning in vocational high schools during the COVID-19 pandemic in West Java Province, Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of Science & Technology, 5(2), 96–107.

https://doi.org/10.17509/ijost.v5i2.24640

Nurfiquah, S., & Yusuf, F. N. (2021). Teacher practice on online formative assessment. Advances in Social Science Education and Humanities Research, 546, 534–538. DOI: 10.2991/assehr.k.210427.081

Ogange, B. O., Agak, J. O., Okelo, K. O., & Kiprotich, P. (2018). Student perceptions of the effectiveness of formative assessment in an online learning environment, Open Praxis, 10(1), 29–39.

https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.1.705

Pace, D. S. (2020). The use of formative assessment (FA) in online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 compulsory education school closure: the Maltese experience. Malta Review of Educational Research, 14(2), 243–271. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/66440

Panday, P. K. (2020, September 2). Online classes and lack of interactiveness. The Daily Sun. https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/502935

Pedersen, C., White, R., and Smith, D. (2012). Usefulness and reliability of online assessments: A business faculty's experience. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 17(3), 33–45.

Perera-Diltz, D., & Moe, J. (2014). Formative and summative assessment in online education. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching, 7(1), 130–142.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education, 2, 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Rigo, F., & Mikus, J. (2021). Asynchronous and synchronous learning of English as a foreign language. Media Literacy and Academic Research, 4(1), 89–106.

Sarita & Dahiya, R. (2015) Academic cheating among students: Pressure of parents and teachers. International Journal of Applied Research, 1(10), 793–797.

Sutadji, E., Susilo, H., Wibawa, A. P., Jabari, N. A. M., & Rohmad, S. N. (2021). Adaptation strategy of authentic assessment in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1810(1), Article 012059. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1810/1/012059

Swedberg, R. (2020). Exploratory research. In C. Elman, J. Gerring, & J. Mahoney (Eds.), The production of knowledge (pp. 17–41). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108762519.002

Vonderwell, S., Liang, X., & Alderman, K. (2014). Asynchronous discussions and assessment in online learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 39(3), 309–328.

Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.001

Xu, H. (2017). Exploring novice EFL teachers' classroom assessment literacy development: A three-year longitudinal study. The Asia Pacific Education Researcher, 26(3–4), 219–226.

Zhang, C., Yan, X., & Wang, J. (2021). EFL teachers' online assessment practices during the COVID-19 pandamic: Changes and mediating factors. Asia Pacific Education Research 30(6), 499–507.

† Bangla is the native language of Bangladesh.↩

Comments

Show All Comments